Earlier this week, I received some comments from a reader regarding my research focus to “understand Chinese comics from the perspective of the present,” included in a previous post on this blog. The reader warned that this position could be interpreted as an expression of “presentism.” In light of this, I thought I might share some of my thoughts on this topic, as it relates to comics studies in China, and elsewhere as well.

As I understand it, “presentism” is a term that is used by historians and other scholars to criticize works appearing to be unduly influenced by the values and interests of their own historical moment. We often call these values and interests “cultural norms”, both in the sense that we tend to think of what we believe and care about to be “normal,” but also in the sense that values and interests shared by large groups of people are typically presented as also being “normative” — a standard to which other members of our society should aspire to.

Historians are primarily concerned with two tasks: first, accurately recording historical events; and second, interpreting the motivations of the historical actors responsible for those events. Presentism is less about the former (which we generally assume to be objective, although Hayden White and others might disagree on this point) and more about the latter. So, for example, a 20th century historian writing a history of Lewis and Clark’s 1803-6 expedition into the “void, the black land of desolation” (as one educational film has it) of the American West “from whence no man, foolhardy enough to venture into it might return” would likely discuss the inclusion of First Nations woman Sacagawea and African-American man York in the “Corps of Discovery [sic].” In our hypothetical historian’s account, they might suggest that Lewis and Clark were as much motivated by practical concerns for guiding, interpreting, and manual labor, as they were by more noble goals, such as protecting Sacagawea and her child from her “loving husband,” the abusive French fur trapper Toussaint Charbonneau. An interpretation along these might ignore or downplay the fact that both Sacagawea and York were enslaved, the former as a young child by a neighbouring tribe (“for the Indians she is less than property”), and the later from birth, as the son of man enslaved by Clark’s father.1

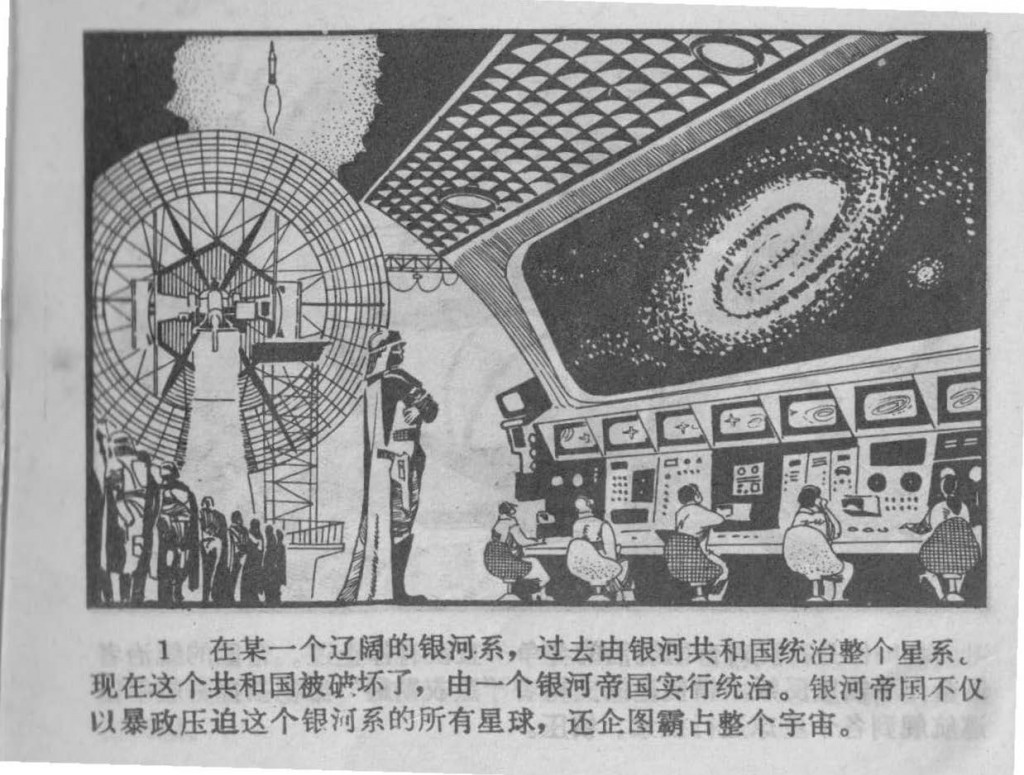

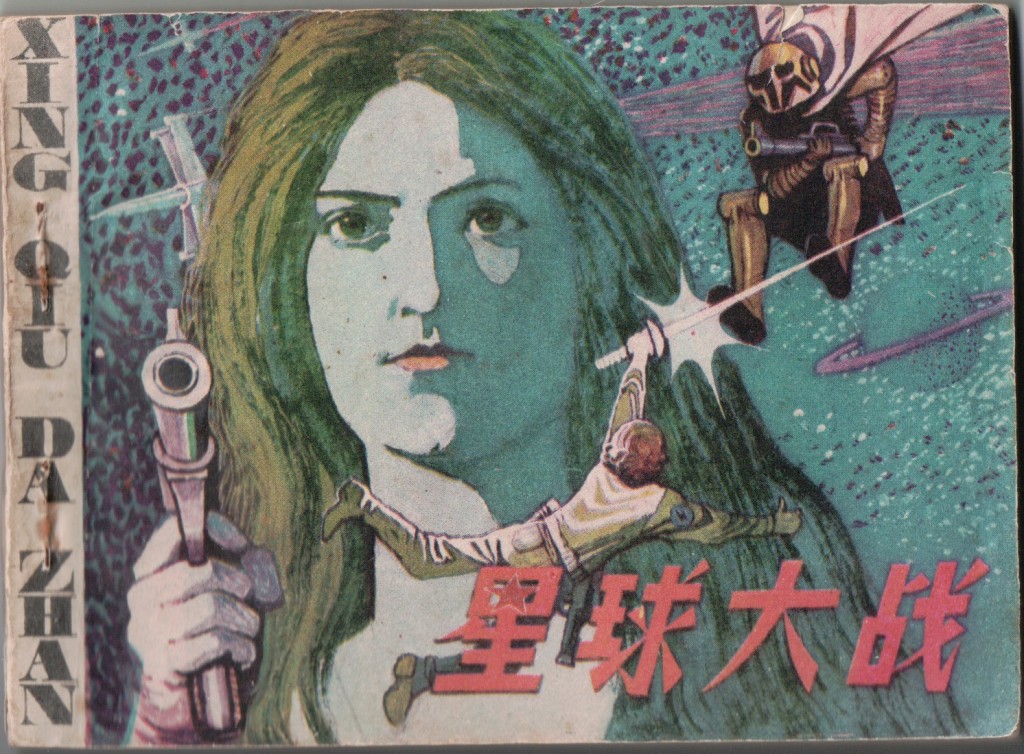

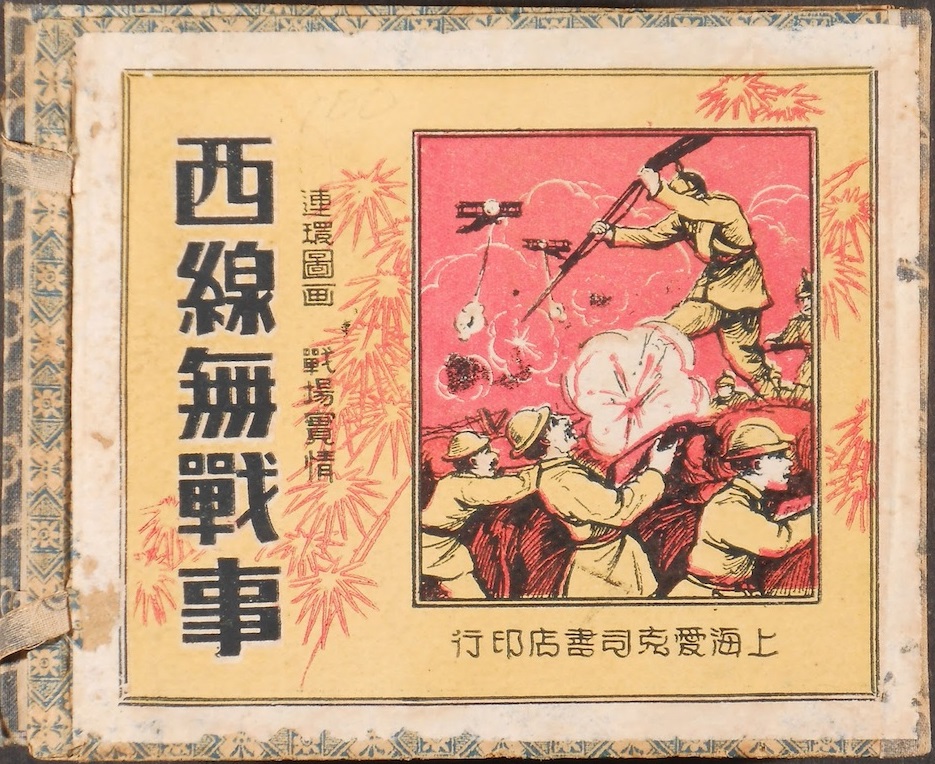

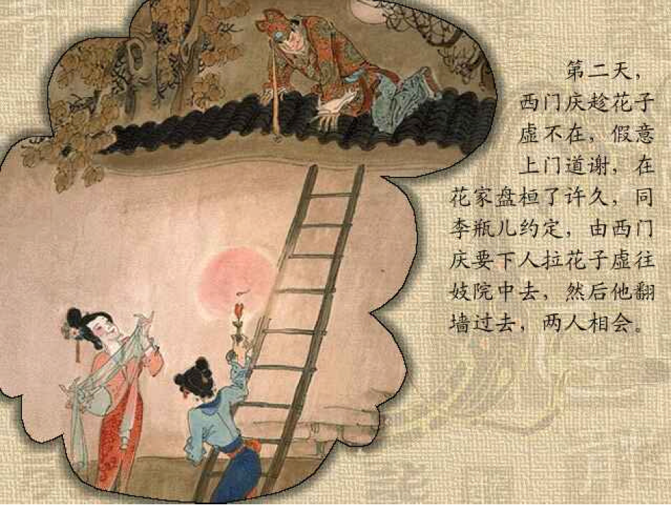

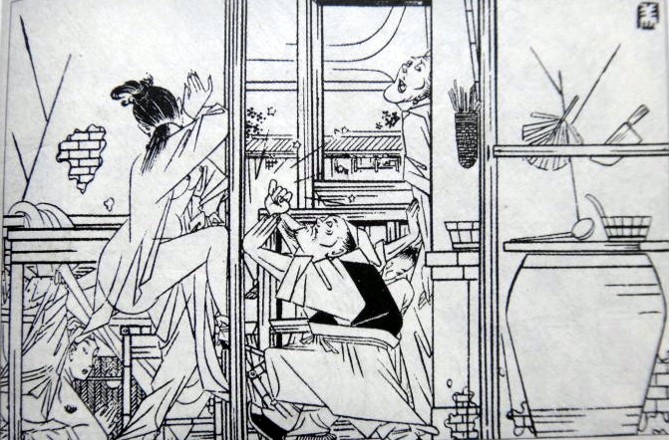

In a sense, presentism is foundational to comics studies, because the term “comics,” as we use it now, only emerged gradually. In its earliest sense, comics referred to cheaply printed humorous illustrated publications, after Thomas Hood’s The Comic Annual, which was published in 11 volumes (skipping a couple of years) between 1830 and 1842. By the 20th century, the term had largely come to refer instead to comic strips, or “the funnies”, published as a supplement in the Sunday papers; and somewhat later, comic books. In his biography of Rodolphe “The Father of the Comic Strip” Töpffer, David Kunzle dances around the term, often referring to Töpffer’s “picture stories,” contained in “comic albums.”2 Although I largely agree with Kunzle that comic strips as they emerged in the 19th century are probably best understood as a “narrative form of caricature,” the fact remains that, even when we can trace a direct line of genealogical descent from “picture story” to “comic strip,” it is unavoidably anachronistic to discuss the emergence of “comic strips” avant la lettre.

- And in fact, the film, released in 1950, omits York and slaves entirely, despite featuring several scenes which take place on plantations. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ck8wASPRwqA [↩]

- David Kunzle, Father of the Comic Strip: Rodolphe Töpffer (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007). [↩]