In my experience learning Chinese over the past decade, one of the biggest challenges I’ve faced is getting enough practice reading (and writing) characters:

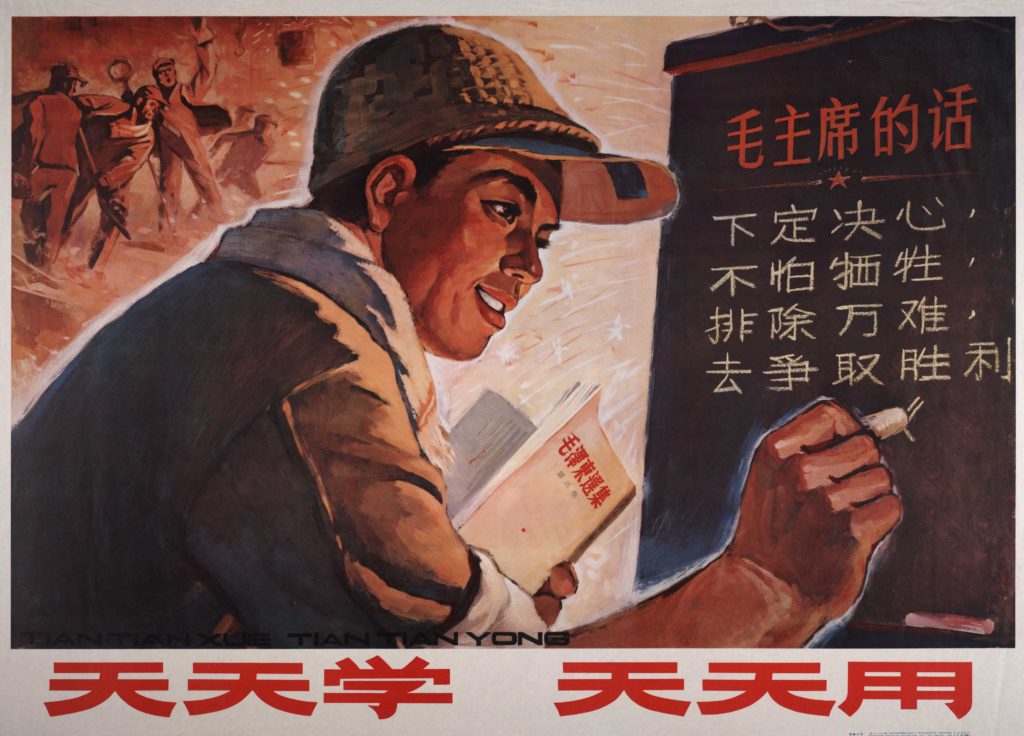

“Study them every day, use them every day” 天天学,天天用 1

Characters take an inordinate amount of time to memorize, and the lack of spaces between words means that proper nouns, set phrases, and foreign transliterations have to be parsed out from the more common vocabulary of everyday writing.

This is the easy answer for why so few Anglophones read untranslated Chinese literature:

Because Chinese is hard.

As the old joke goes, though:

Q: What’s the difference between ignorance and apathy?

A: I don’t know and I don’t care!

My suspicion is that there are a lot of people out there like me — people who are being held back not so much by the difficulty of learning Chinese, as by the difficulty of finding things to read in Chinese, so that we can actually get the practice we need to become (and stay) functionally literate.

Ignorance and apathy are self-perpetuating, of course: The less one reads in Chinese, the harder it is to pick up a book or story to read casually.2

At the same time, one hears over and over again that nothing worth reading is being published in China today. Just a couple of days ago, Ha Jin, an author who I respect and admire, was quoted on LitHub saying that, “Many of my novels—A Free Life, War Trash, A Map of Betrayal—which have political resonance, are not allowed to published.”3 Can Xue has gone even further, saying, when asked about contemporary Chinese literature, “I have no hope, and I don’t feel like evaluating it.”4

Setting aside, for the moment, questions of censorship and literary merit (which seem to, somewhat conveniently, to do double duty as pitches for dissident lit), genre fiction—particularly short fiction—provides interesting examples of ‘marginal’ or ‘weird’ literature: the queer, the dystopian, the creepy.

The trick is finding it.

- ‘Them’ here isn’t actually characters, it’s ‘the words of the Chairman Mao’ but same diff, right? [↩]

- In language acquisition studies, this is referred to as ‘attrition’ and it probably affects us more than we think, since most of us have a pretty high tolerance for reading words that we don’t entirely understand. It’s more obvious when it comes to spelling (or writing characters), especially when we’re deprived of spell check (and IMEs). Two related concepts are the ‘plateau effect,’ which points to the fact that we learn L2 languages in stages, rather than all at once, and ‘fossilization,’ which refers to becoming trapped at a sub-fluent level. [↩]

- Ha Jin on the Long Reach of the Chinese Government: Love, Betrayal, and the Totalitarian Machine [↩]

- Q&A with Author Can Xue on the State of Chinese Literature [↩]