Few figures in Chinese mythology seem better suited to being adapted to cartoons than the Monkey King, Sun Wukong 孙悟空:

Source: James Khoo Fuk-lung’s (邱福龍) The Sage King,Issue 1, 2002.

Certainly, Nezha 哪吒 has found some success through his own films and cartoons, such as the classic 1979 Cultural Revolution parable, Nezha Conquers the Dragon King 哪吒闹海. And arguably Guangyu 關羽 , Zhuge Liang 諸葛亮, and Liu Bei 劉備 etc of popular video games such as Dynasty Warriors 真‧三國無双 and manhua series such as Lee Chi Ching’s 李志清 Record of the Three Kingdoms 三國志 share more in common with their mythological counterparts of Chinese folk religion than they do with the real-life historical figures whose names they borrow.

Even so, Sun Wukong surpasses them all. Reading his exploits in the Ming vernacular novel Journey to West 西游記 brings to mind a Looney Toon or Silly Symphony, some 500 years before Bugs Bunny ever delivered his first wisecrack. Consider the following passage:

“Since hearing the Way,” Sun Wukong said, “I have mastered the seventy−two earthly transformations. My somersault cloud has outstanding magical powers. I know how to conceal myself and vanish. I can make spells and end them. I can reach the sky and find my way into the earth. I can travel under the sun or moon without leaving a shadow or go through metal or stone freely. I can’t be drowned by water or burned by fire. There’s nowhere I cannot go.”1

In another, even more graphic passage, Monkey brags:

Cut off my head and I’ll still go on talking,

Lop off my arms and I’ll sock you another.

Chop off my legs and I’ll carry on walking,

Carve up my guts and I’ll put them together.

“When anyone makes a meat dumpling

I take it and down it in one.

To bath in hot oil is really quite nice,

A warm tub that makes all the dirt gone.2

Indestructibility is of course, is perhaps the defining characteristics of a cartoon, brought to it’s logical conclusion by The Simpsons’ classic cartoon-within-a-cartoon, The Itchy and Scratchy Show:

Like Itchy and Scratchy, Sun Wukong makes the ultra-violence of Anthony Burgess’ A Clockwork Orange look tame by comparison. To give just one of innumerable examples, consider the following scene in Chapter 44 of Journey to the West when Sun Wukong is gets fed up with asking two Taosist priests to let a group of 500 captured Buddhist monks go:

“We couldn’t possibly let them go,” the priests said.

“You couldn’t?” said Monkey.

“No,” the priests replied. By the time he had asked this and been given the same answer three times he was in

a terrible rage. He produced his iron cudgel from his ear, created a spell with his hands, made it as thick as a

rice bowl, swung it, and brought it down on the Taoists’ faces. The poor Taoists

Fell to the ground with their blood gushing out and their heads split open,

Wounds that were gaping wide, brains scattered everywhere, both necks broken.3

Finally, like any cartoon character worth his salt, Monkey uses his violent superpowers for comic effect. In Chapter 46 of Journey to the West, Monkey matches wits with a Taoist known as ‘Tiger Power, Senior Teacher of the Nation.’ When Monkey overhears Tiger Power boasting that he can have his heart cut, his head cut off, and is able bathe in boiling oil, all without dying, Monkey offers to have his own head cut off if Tiger Power is willing to do the same. Tiger Power agrees, but after Monkey is bound and beheaded, Tiger Power tries to play a trick on him by having a local deity use magic to prevent Monkey’s head from rolling back to his body when he calls for it. Monkey, Master of the 72 Transformations, does him one better, however, by growing a new head. The King, who has been holding Monkey and his fellow travelers hostage, is forced to issue a passport to allow them to leave the kingdom. Monkey responds by saying:

“We accept the passport, but we insist that the Teacher of the Nation must be beheaded too to see what happens!”

“Senior Teacher of the Nation,” said the king, “that monk’s not going to let you off. You promised to beat him, and don’t give me another fright this time.” Tiger Power then had to take his turn to go to be tied up like a ball by the executioners and have his head cut off with a flash of the blade and sent rolling over thirty paces when it was kicked away.

No blood came from his throat either, and he too called out, “Come here, head.”

Monkey instantly pulled out a hair, blew a magic breath on it, said, “Change!” and turned it into a brown dog that ran across the execution ground, picking the Taoist’s head up with its teeth and dropping it into the palace moat.

The Taoist shouted three times but did not get his head to come back. As he did not have Monkey’s art of growing a new one the red blood started to gush noisily from his neck.

No use were his powers to call up wind and rain;

He could not compete with the true immortal again.

A moment later his body collapsed into the dust, and everyone could see that he was really a headless yellow−haired tiger.4

Add to his indestructibility, willingness to commit violence, and acerbic wit the fact that Journey to West is a foundational text in not only China, but also 20th century pop-culture powerhouses Korea and Japan, and it is perhaps not surprising then, that the Monkey King has appeared in literally dozens of animated films, comic books, and live-action TV shows over the past 100 years. Here are three of my favorites:

1. Princess Iron Fan 鐵扇公主 (1941)

The granddaddy of all Monkey King adaptations, I’ve written a little about the Princess Iron Fan before, and the influence it had on a young Osamu Tezuka. Princess Iron Fan was created by the twin brothers, Wan Laiming 万籁鸣 (1900-1997) and Wan Guchan 萬古蟾 (1900-1995), who had previously produced short animations in the style of Walt Disney’s Silly Symphonies. The Disney influence on their first feature film is especially obvious, although (as we will see) they achieved greater stylistic independence in their later films.

Thanks to the wonders of the Internet, entire film is available on YouTube, with English language subtitles:

At the time, Laiming and Guchan were criticized for returning to Japanese-occupied Shanghai to produce the film at Zhang Shankun’s 張善琨 New China Film Studios 新華影業公司, the sole reminder of Shanghai’s once flourishing film industry following the Battle of Shanghai in late 1937. Although the film enjoyed a successful run in Japan (as evidenced by Osamu Tezuka’s enduring childhood memories of the film), with few Chinese having seen it during or after the war, film scholars have argued that Laining and Guchan were subtly trying to inspire the Chinese people to resist the Japanese just like Monkey resists the feminine wiles of the eponymous Princess Iron Fan, and one can imagine that the brothers themselves made similar arguments to their critics while in semi-exile in Hong Kong during the late 1940s.5

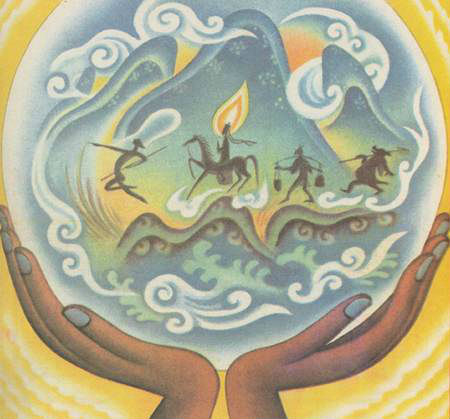

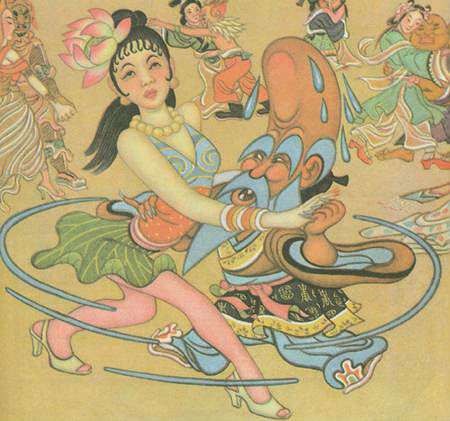

2. Manhua Journey to West 西游漫記 (1945)

An overlooked masterpiece, and my personal favorite cartoon version of Monkey, Zhang Guangyu’s 張光宇 (1900-1965, née Zhang Dengying 张登瀛) Manhua Journey to the West uses the framework of Monkey’s tale to create biting satire of the KMT-run Nationalist government during the Second Sino-Japanese War. It is also happens to be a work of critical importance to history of Chinese cartooning, as it bridges the gap between the pre-war cartoons of the late 1920s and 1930s and the Cold War-era cartoons of the 1950s.

EDIT 1/25/15: For the sake of bringing this out-of-print work to a wider audience, I’ve started translating Zhang’s entire 60 page comic into English here.

Like many cartoonists of his generation, Zhang Guangyu came to cartoons in a roundabout fashion. Born into a family of traditional Chinese doctors in 1900 in Wuxi 無錫, a city in southern Jiangsu province about 140 km east of Shanghai, Zhang moved to Shanghai to attend school when he was 14 years old. As an opera fan, he got to know the actor Zhang Delu 張德禄 at the New Stage 新舞台 where he got his start doing make-up and sketches of operas. When Zhang graduated from elementary school two years later, he used his connections with the New Stage to become a student of the set designer and painter Zhang Yuguang 張聿光.6 In 1918 he moved into publishing, becoming the assistant of the pioneering Chinese cartoonist Ding Song丁悚 (1891-1972) who at the time was working for World Pictorial 世界畫報 published by the Sheng Sheng Fine Arts Company 生生美術公司. Over the next two decades, Zhang would go on to co-found the many of the most important mutual-aid organizations and publications for Chinese cartoonists, along with his brothers Cao Hanmei 曹涵美 (1902-1975, nee Zhang Meiyu 張美宇?) and Zhang Zhengyu 張正宇 (1904-1976, nee Zhang Zhenyu 張振宇).7

When he created Manhua Journey to West, however, Chinese cartooning had been almost entirely subsumed into the production of anti-Japanese propaganda. While Manhua Journey to the West contains elements of this, it is also one the first examples I’ve been able to find of an original extended narrative being told with cartoons in China. Prior to Zhang’s 1945 work, most Chinese cartoons are either single or multiple panel gag strips, or relatively faithful adaptations of classic tales, such Cao’s 1942 lianhuanhua adaption of Jin Ping Mei. Zhang however, does something totally new (at least for comics) in Manhua Journey to West by taking the Sun Wukong readers knew and loved, and placing him in a thinly veiled pastiche of Chongqing, circa 1945:

Without realizing it, they arrived in a place called the City of “Sweet Dreams,” 梦得快乐城 this was the wealthy part of Ey-qin 埃秦, where everyone lived a life a luxury, and all of the people coming and going from this mountain city were aristocrats and prominent officials, millionaires and billionaires, in addition to the elegant ladies and dancing girls of Ey-qin, all of them were on display in this place.8

Much like the original Journey to the West, Manhua… is episodic in nature, with Zhang dividing the narrative up into ten chapters. Originally displayed the work at an exhibition in Chongqing in November, 1945, in February of the next year it was put on display in Chengdu, and by May it had arrived in Shanghai. Shortly thereafter it was banned by KMT officials. Around the same time, Zhang accepted a job in Hong Kong as an art director for Dazhonghua Film Studio 大中華電影片公司, joining the flood of capital and skilled labor flowing out of Shanghai and into Hong Kong during last years of the Civil War. In the summer of 1947 a third exhibition of Manhua Journey to the West was organized in Hong Kong, but was not until 1958 that the collection of 60 drawings with about 7000 characters of text was finally published in book form. Zhang, by then having returned to the Chinese mainland, relied heavily on this work while working on the character designs for perhaps the most well-known Chinese adaptation of the Monkey King, the 1964 animated film Uproar in Heaven 大闹天宫.

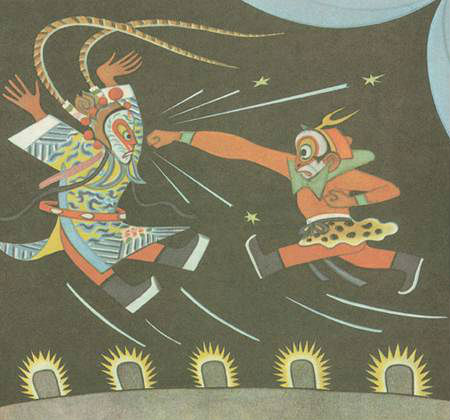

3. Uproar in Heaven 大闹天宫 (1964)

Produced at the infamous Shanghai Animation Studio 上海美術電影製片廠 under cartoonist-turned-animator Te Wei 特偉 (1915-2010), and directed by none other than Wan Laiming, the production team of Uproar in Heaven reads like a dream team of Chinese cartoonists and animators. It is perhaps the only Chinese animated film to be widely known in English-speaking countries, and like Princess Iron Fan it is available in it’s entirety on YouTube with English subtitles:

Due no doubt in no small part to Zhang Guangyu’s influence, Wan Laiming’s second attempt at creating an animated Monkey King shows an obvious debt of inspiration to traditional depictions of Sun Wukong in Chinese opera, not only visually, in make up and costumes, but also in movements and staging. Add to this the obviously operatic musical score, composed by Wu Yingju 吳應炬 and performed by the Shanghai Film Studio Orchestra 上影樂團 and the Shanghai Peking Opera Orchestra 上海京劇院樂隊, and it is clear that Uproar in Heaven represents the culmination of Te Wei’s 1956 exhortation to “Seek out a Chinese national style of animation!”探民族風格之路.9 Supposedly written on the wall of the studio during the production of The Proud General 骄傲的将军 (1957), Te Wei’s slogan marks a shift away from Disney-style animations of talking animals and toward more authentically Chinese styles of animation, such as ink painting and paper cut.

When the first half of Uproar in Heaven was shown in 1961 during the relative “cultural thaw” of the early 1960s PRC, it received widespread praise. By the time the second half of the film was completed in 1964, foreshadowings of the impending Cultural Revolution had led to the film being banned for supposedly satirizing Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party, with the majority of the “dream team” of artists, many of whom were nearing retirement, being sent into the countryside to do forced labor for over a decade. Following the Cultural Revolution, however, the film was re-released, sparking a second renaissance of Chinese animation in the 1980s, with classic films like The Gourd Brothers 葫 蘆兄弟 (1987), Captain Black Cat 黑貓警長 (1984-87), and Ah Da’s Three Monks 三個和尚 (1980). Although several new cartoon versions of the Monkey King appeared in the 1990s and 2000s, among them a series which borrowed the name (but nothing else) from Zhang Guangyu’s Manhua Journey to the West, so far none have been able to rival the 1964 version’s overwhelming popularity.10

- Wu, Cheng’en. Journey to the West. Translated by W. J. F. Jenner. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 2003, Chapter 3. [↩]

- Wu, Cheng’en, Chapter 46. [↩]

- Wu, Cheng’en, Chapter 44. [↩]

- Wu, Cheng’en, Chapter 46. [↩]

- See for example Chiu, Monica. Drawing New Color Lines: Transnational Asian American Graphic Narratives. Hong Kong University Press, 2014, pg. 113 [↩]

- No relation as far as I’m aware, but his pen name seems to have been meant as an homage. [↩]

- See the timeline of Zhang’s life provided in “Suzhou Museum: Manhua Journey to the West – Zhang Guangyu Retrospective” 苏州博物馆 西游漫记——张光宇艺术作品展, n.d., http://www.szmuseum.com/default.php?mod=article&do=detail&tid=4038 (accessed December 7, 2014). [↩]

- 張光宇. Manhua Journey to the West. 1st ed. People’s Fine Arts Press 人民美术出版社出版, 1958, pg. 15. [↩]

- See Te Wei “特伟,” http://www.js.xinhuanet.com/zhuanlan/2005-03/24/content_3935971.htm. [↩]

- This of course, conveniently overlooks the Super Saiyan in the room–Akira Toriyama’s 鳥山明 1985 manga series Dragon Ball and it’s various spinoffs. Dragon Ball, known as “Dragon Pearls” 龍珠 in mainland China, seems to have wildly popular during it’s heyday, since most Chinese people in their 20s and 30s that I’ve asked about it seem to be familiar with the show. The reception of a Japanese anime and manga in China is probably something that deserves an entire post in it’s own right, however, especially when one considers the back-borrowing that has occurred with Hong Kong wuxia comics like James Khoo Fuk-lung’s The Sage King, random graffiti artists in the UK and of course, Jamie Hewlett and Damon Albarn‘s virtual band Gorillaz, with the latter two perhaps also owing a debt of inspiration to the BBC-produced English-language dub of the live action Japanese TV series Monkey 西遊記. [↩]

Pingback: Zhang Guangyu's Manhua Journey to the West (1945) - Part 1 of 6 - Nick Stember

Pingback: Zhang Guangyu’s Manhua Journey to the West (1945) - Part 2 of 6 - Nick Stember

Pingback: Zhang Guangyu's Manhua Journey to the West (1945) - Part 3 of 6 - Nick Stember

Pingback: Zhang Guangyu's Manhua Journey to the West (1945) - Part 4 of 6 - Nick Stember

Pingback: Zhang Guangyu’s Manhua Journey to the West (1945) – Part 5 of 6 - Nick Stember