Between World War I and World War II China experienced it’s first boom in the production and appreciation of cartoons and manhua. Although several notable cartoon and proto-cartoon publications predate World War I (and more importantly in China, the collapse of the Qing in 1911),1 it is the 1920s and 1930s which saw comic strips and cartoons reach their highest social currency in China, one that has perhaps yet to be rivaled even today.

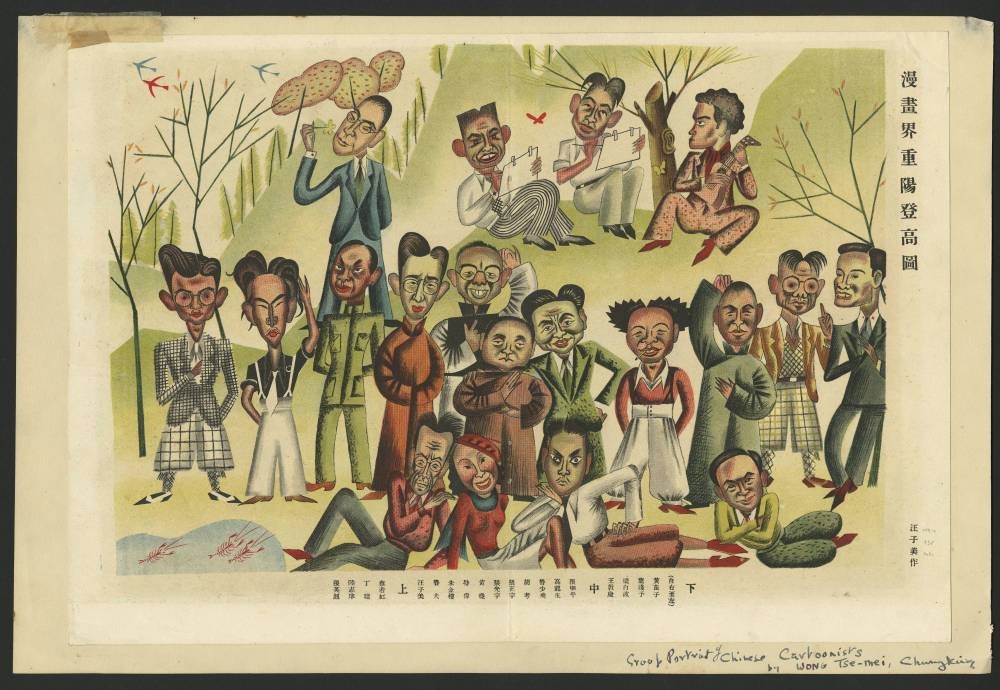

In large part this is thanks to the work of a group of loosely affiliated artists, writers, and publishers who collaborated on several key publications produced primarily (but not exclusively) in Shanghai. Many of them are featured in this 1936 illustration by Wang Zimei , :

The cartoon circle climbs the mountains for Double-Ninth 漫畫界重陽登高圖

According the caption, they are (from left to right):

Bottom row: Wang Dunqing王敦慶 (1899-1990), Liang Baibo 梁柏波 (?1911-70),Ye Qianyu 葉淺予 (1907-95), Huang Miaozi 黃苗子 (1913-2102)

Middle row: Wang Zimei 汪子美, Lu Fu 魯夫, Zhu Jinlou 朱金樓, Te Wei 特偉 (1915-2010), Huang Yao 黃堯 (1917-87), Zhang Guangyu 張光宇(1902-65), Zhang Zhengyu 張正宇 (aka Zhang Zhenyu 張振宇 1903-76), Hu Kao 胡考 (1912-94), Lu Shaofei 魯少飛 (1903-95), Gao Longsheng 高龍生, Zhang Leping 張樂平 (1910-92)

Top row: Zhang Yingzhao 張英趙 ,Lu Zhixiang 魯志庠,Ding Cong 丁聰 (1916-2009), Cai Ruohong 蔡若虹 (1910-?)2

As I am currently in the process of writing my MA thesis on the networks of economic and social capital which made manhua periodicals possible during this time period,3 most of these names are very familiar to me. Wang’s illustration, however, is the first time I’ve seen them all in one place.

- For example The China Punch was an early cartoon magazine produced in Hong Kong, and Puck, or the Shanghai Charivari the Dianshizhai Pictorial 點石齋畫報 were both published in Shanghai durin the last decade of the 19th century. For more on China Punch and Puck, or the Shanghai Charivari see Christopher Rea’s essay “He’ll Roast All Subjects That May Need the Roasting’: Puck and Mr Punch in Nineteenth-Century China.” in Asian Punches, edited by Hans Harder and Barbara Mittler, 389–422. Berlin: Springer, 2013. For more on the Dianshizhai Pictorial, see Rudolph Wagner’s chapter “” in Joining the Global Public: Word, Image, and City in Early Chinese Newspapers, 1870–1910 . Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007. [↩]

- Dates and image courtesy of Mary Ginsberg and Paul Bevan at the British Museum. who included this image among others collected by Jack Chen in the exhibition The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda, on display May-Sep 2013. [↩]

- The research question I am trying to answer is: For what reason (or reasons) did manhua magazines cease publication in 1930s Shanghai? I believe that I can plausibly answer this question by completing a close reading of a selection of manhua periodicals, combined with biographical research into the contributors and publishers, and historical research into the economic and political realities of 1930 Republican era China. Another way to put this is that I am attempting to write a typology of failure for manhua magazines, ergo my working title “ [↩]