As many of you already know, I am on track to graduate from the Department of Asian Studies at UBC with my Masters degree in August. After a lot hand wringing, I’ve decided to take a year off from graduate school to devote myself to translation and other projects. I’m not sure if I will continue on to a PhD at the end of the year or not.

The good news: I’m still head over heels in love with Chinese comics, and plan to continue blogging and tweeting far, far into the foreseeable future. Here are the Chinese manhua and lianhuanhua that I plan to translate over the next six months to a year, depending other obligations (like eating, sleeping, paying the rent, etc) that life throws my way. Also, if you have any suggestions for future projects, or would like to donate to support my translations, there is a page for that now!

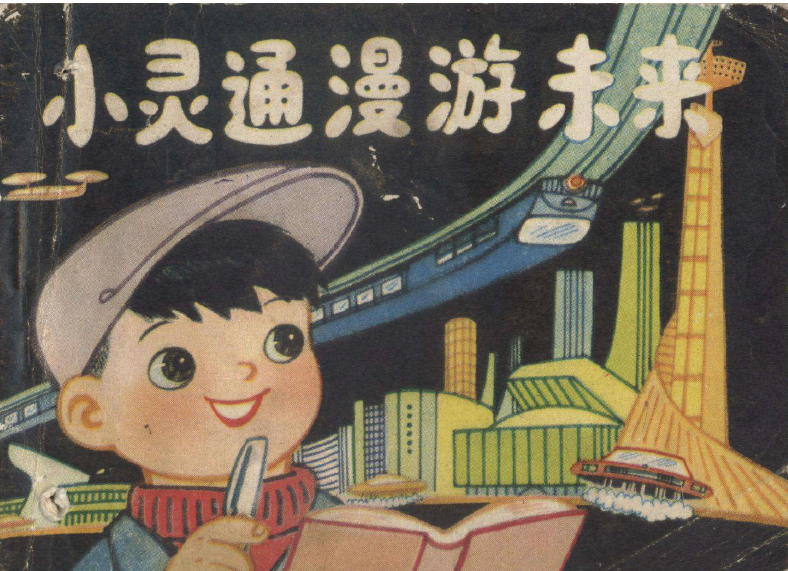

1. Smarty Pants Visits the Future 小靈通漫遊未來

Adapted by Pan Caiying 潘彩英 from the original 1978 story by Ye Yonglie 業永烈 with art by Du Jianguo 杜建國 and Mao Yongkun 毛用坤.

(Liaoning Fine Arts Press 遼寧美術出版社, May, 1980, 150 pages)

Description: Popular lianhuanhua adaptation of a groundbreaking post-Cultural Revolution sci fi story. A young boy visits the near future and learns about all of the amazing new technologies which will make life easier for the Chinese people, including smart watches, robot butlers, hover cars, and (of course) giant watermelons.

Think The Jetsons meets EPCOT as imagined by Deng Xiaoping.

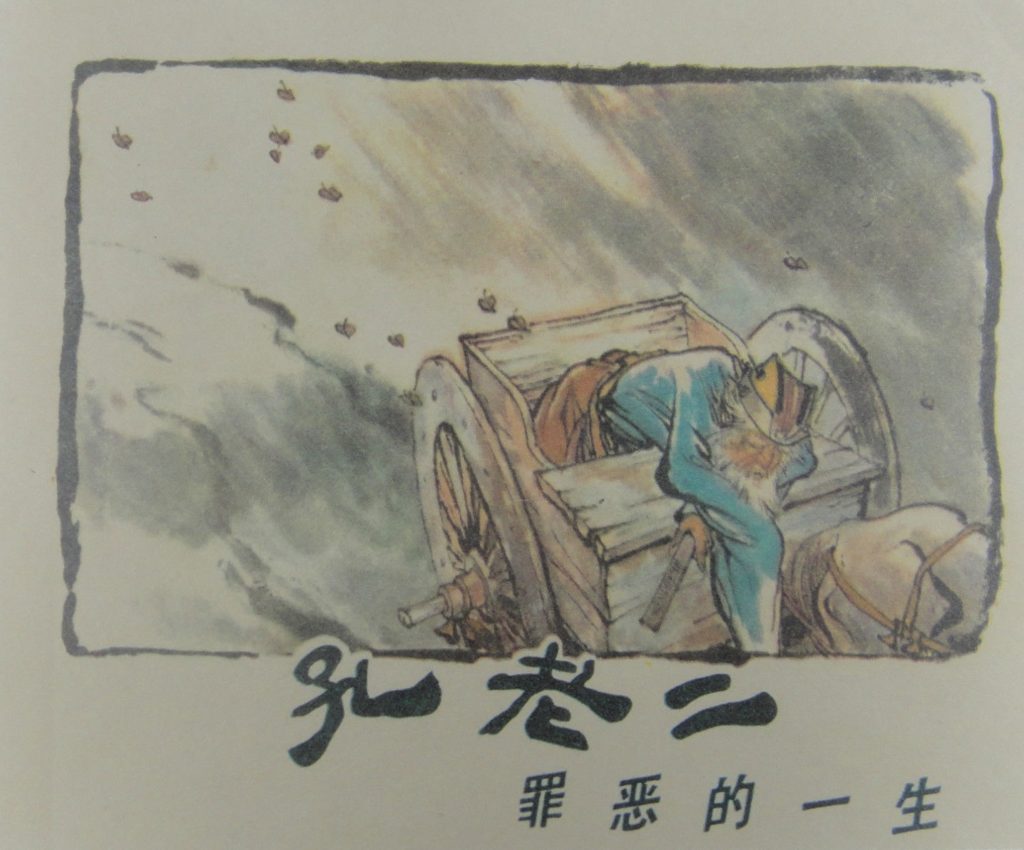

2. Confucius: A Life of Crime 孔老二 罪恶一生

Xiao Gan 萧甘 with art by Gu Bingxin 顾炳鑫 and He Youzhi 贺友直

(People’s Press Shanghai 上海人民出版社, June, 1974, 23 pages)

Description: This short comic was produced towards the end of the Cultural Revolution as part of the 1974 “Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius” campaign launched by the Gang of Four. Sharply critical of the ancient philosopher whose teachings (or interpretations thereof) have come to be seen as foundational to Sinophone countries, this irreverent look at the man from Qufu is one of the more light-hearted products of the disastrous Cultural Revolution.

Think O Brother Where Art Thou meets The Devil’s Dictionary as imagined by Christopher Hitchens.