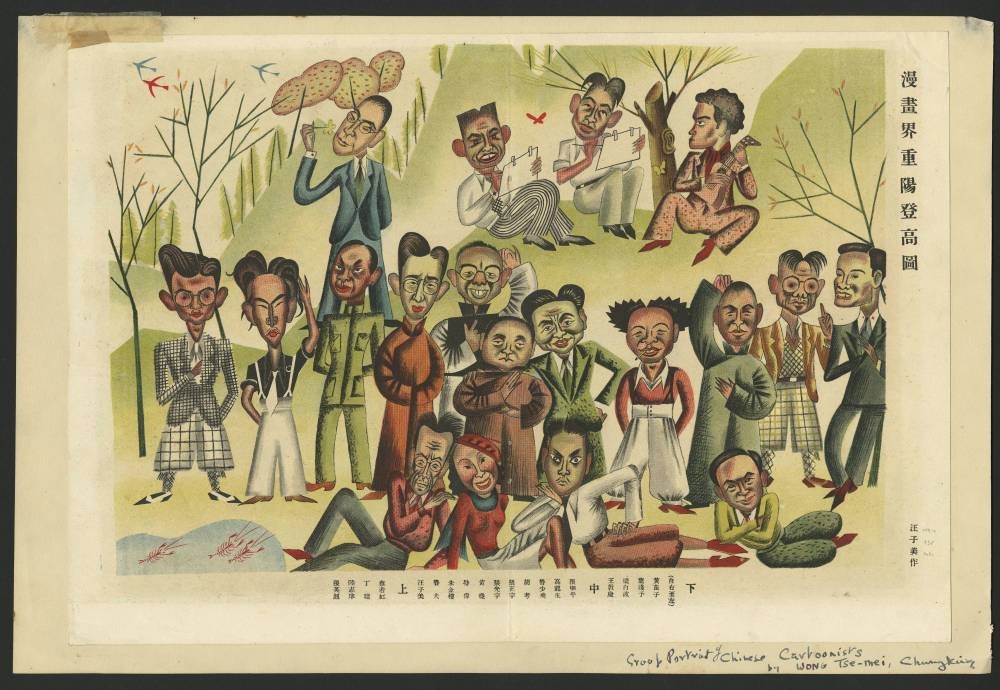

Zhang Guangyu’s 張光宇 (1900-1965) overlooked masterpiece, Manhua Journey to the West 西遊漫記 was originally created in the fall of 1945 while Zhang was living in the wartime capital of Chongqing. Deeply critical of the ruling KMT government, it was eventually banned and did not see print for another 13 years. For the sake of introducing Zhang’s out-of-print work to a larger audience, I’ve taken the liberty of translating the entire 60 page comic into English and will be posting it in installments on my blog over the next several weeks.

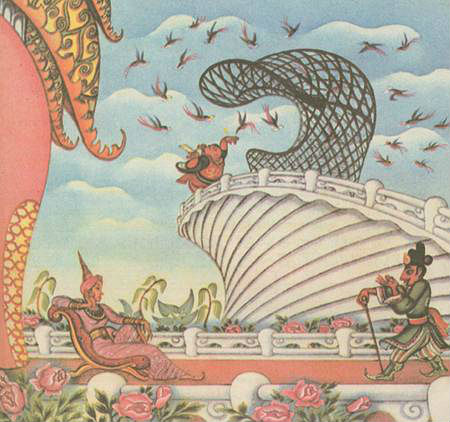

In part 2 of this 6 part translation, Monkey and Zhu Bajie run into Lady Mengjiang, who husband has been forced to labor on the wall.1 Monkey promises to seek vengeance and with the help of a crow monster, he and Zhu Bajie are able to track down the Crested Falcon. A battle takes place and Monkey handily dispatches his foe, freeing his master and Brother Sand. The four pilgrims continue on the “City of Sweet Dreams” 梦得快乐城2 above which floats the Pharaoh’s spectacular palace of air balloons, the Epang Palace 阿房宫.3 The mayor of the City of Sweet Dreams agrees to take the four pilgrims up into the Epang Palace in an elevator, but Monkey is impatient, so he flies ahead on his magic cloud only to find himself face to face with an army of monsters and, possibly even worse, hairdressers…

21. 孙 悟空朱八戒走在前面,行了一程,只不见师傅与沙和尚随来,心中有些疑惑,孙猴知道有变,一个筋斗云翻上半空,四面一望,并无动静,但见半山腰有一白衣女子 正在哭哭啼啼的喊:“好命苦,我的丈夫,今番又被拉去当壮丁,叫我如何过活呀!……”十分凄切,悟空踏住云脚,翻身落地,上前打问,原来她叫孟姜女,她的 丈夫范杞良是万年老丁,回为没有钱今番又被鸦鸦鸟们奉了毛尖鹰之命强拉去当新丁!孙猴听了,十分愤怒道:“我齐天大圣与你们报仇!”孟姜女拜谢不已。

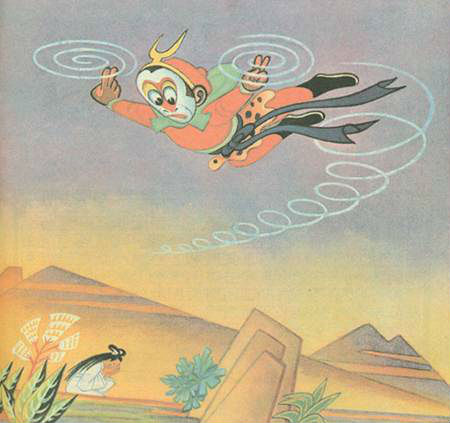

Sun Wukong and Zhu Bajie went ahead, but they couldn’t find their master or Brother Sand, so they began to feel uneasy. Sun Wukong knew that something was the matter, so he jumped on his magical cloud and sprang up into the sky, looking all around, but no one was out and about. Then all of a sudden halfway up the mountain he saw a woman in white, sobbing and crying out, “Life is so unfair, today my husband was taken away to be conscripted, how can I ever go on!?” Completely at a loss, Sun Wukong stopped his cloud, and turned around to coast to earth. Going up to ask her what was up, he found out she was called Lady Meng Jiang. Her husband, Fan Qiliang, was an old laborer of many years, but because he didn’t have any money he was once again conscripted by the Crow-crow Birds to become a new laborer! Upon hearing this, Sun Wukong was filled with rage and said, “I, the Great Sage Equal of Heaven will take revenge on your behalf!” Whereupon Lady Meng Jiang thanked him profusely.

22. 且说朱八戒在地面上四处探寻师傅的下落,却一无所得,正在纳闷,忽然路边踱来一只鸟鸦小黑精,嘻皮笑脸的,八戒喝住道:“你见到两个和尚否?”小黑精答道: “有的,有的,听说已经陷入地牢。”八戒问道:“有何解救办法?”小黑精打手作势意思要钱,八戒会意,连说:“这有何难,要多少便与你多少!”

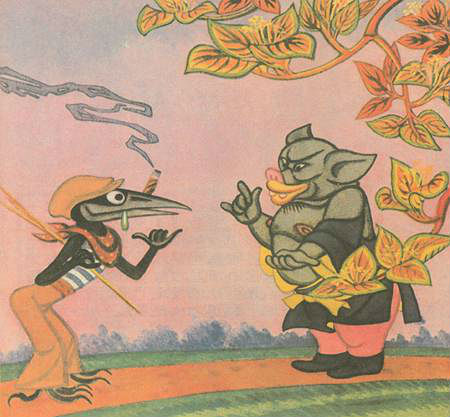

Meanwhile, Zhu Bajie was looking all around for their master’s whereabouts, but he had come up empty handed. At his wits end, a little black crow monster came strolling past, laughing and smiling, so Zhu Bajie shouted at him, “Have you seen two monks?” The little black monster replied, “I sure have. I heard that they’ve already been put in the underground prison.” Bajie asked him, “Is there any way that I can rescue them?” The little black monster made a gesture with his hand, indicating he wanted money. Bajie caught his drift right away, saying, “What’s the big deal? However much you want, I’ll give it to you!”

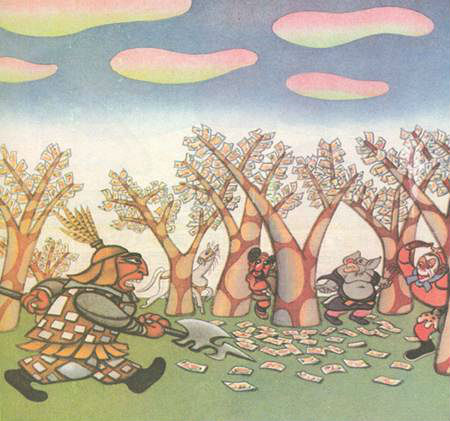

23. 两 个正在谈得合缝,半空中孙悟空懊丧而回,八戒高兴道:“有着落了。”……于是悟空八戒随着小黑精同去辨理“赎丁”手续。行至一处,只见一连串的人,被众鸟 鸦精牵着,绳捆钱锁,郎当而行,正见三藏师傅与沙僧也杂在中间,悟空见了咆哮一声叫:“众小妖们慢走!”举起金箍捧[棒?]见一个黑精便打死一个,打得满地是黑 尸,像打翻了炭篓子一样。

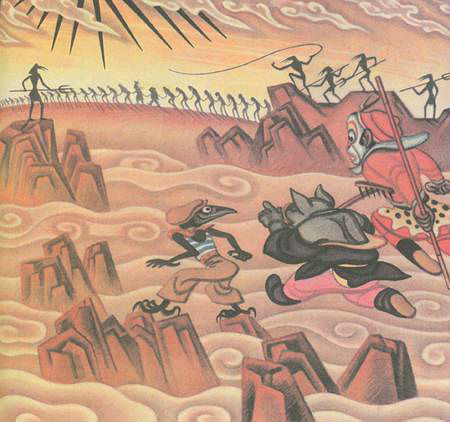

Just as the two of them were finishing their deal, a despondent Sun Wukong suddenly appeared. Bajie happily said, “I know where they are.” Whereupon Sun Wukong, Bajie, and the little black monster all went together to redeem the captives. They arrived in a place where they saw a linked chain of laborers being leady by the Crow-Crow bird monsters. The prisoners were all tied together, making their dispirited way. Upon seeing that Tripitaka and Brother Sand had been mixed in with the rest, as well, Sun Wukong let out a roar and said, “Not so fast you little demons!” Taking up his golden-banded staff, he struck dead every black monster he saw, until the ground was covered with black corpses, exactly as if he had overturned a basket of coal.

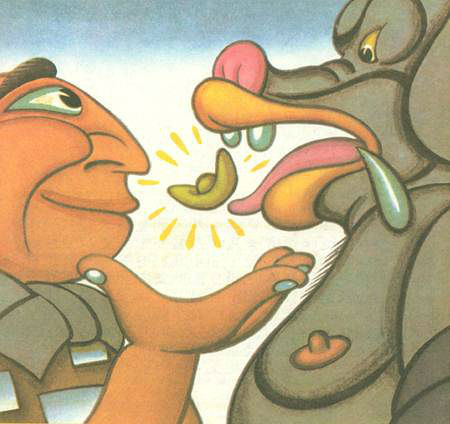

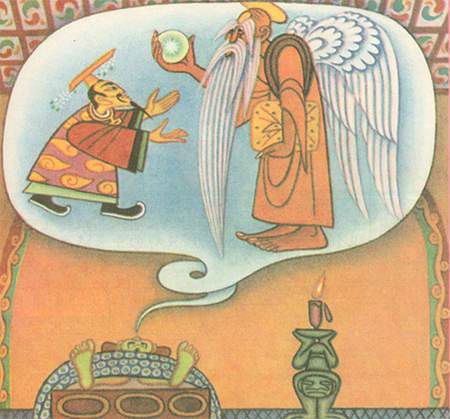

24. 悟 空救了三藏沙和尚及众弱丁,一不做,二不休,一路打进毛尖鹰的衙门来,毛尖鹰急披甲带胄,提枪出阵迎战,两个斗了三十余回合,毛尖鹰有些抵挡不住,急摇身 一变,往空中一纵,现出三头六臂,手持各式刑具,扑将过来;这里孙大圣那里肯示弱,也显出本领,现出三头六臂的巨神,手中有一件宝器,叫做“众心铁链正义弹”抛将过去,果然把那恶魔毁灭了。

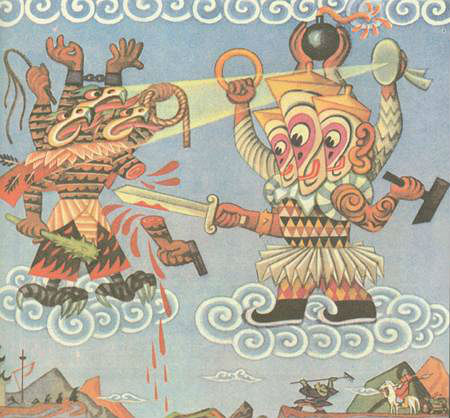

Wukong saved Tripitaka, Brother Sand, and the many powerless laborers as well. In for a penny, in for a pound, he battled his way into the office of the Crested Falcon who hurriedly put on armor and donned his helmet, picking up a gun to go out and meet his enemy. The two battled for thirty rounds, but the Crested Falcon was outmatched, so he shook his head and grew up into the sky, appearing before them as a giant being with three heads, and six arms. In his hands he held a variety of implements, which he threw at Wukong. Not wanting to appear weak, the Great Sage Su Wukong also showed off his abilities, likewise turning into a giant with three heads and six arms, two of which held a jeweled device called “The Righteous Cannonball of the Iron Chain of the Hearts of the Masses.” With this weapon he was able to destroy the monster Crested Falcon.

- This is a famous Chinese legend whose origins can be found in the Zuozhuan commentary to the Spring and Autumn Annals, compiled in the third or fourth century BC. See Wilt Idema’s Meng Jiangnü Brings Down the Great Wall : Ten Versions of a Chinese Legend. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008. [↩]

- In his 1958 introduction to the print version, Zhang comments that the City of Sweet Dreams was meant to be stand-in for the “decadent and dissolute life in the interior during the war.” A somewhat garbled translation is available here. [↩]

- This is the name of a famously grandiose palace which Qin Shihuang began construction on in 212 BC but was never completed. See Lukas Nickel, “The First Emperor and Sculpture in China,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 76, no. 03 (October 2013): 26. [↩]