The Jin Ping Mei 金瓶梅1 is a notoriously pornographic vernacular Chinese novel believed to date from the late sixteenth century. Authored during the disastrous reign of the Wanli Emperor 萬里 who posterity has come to remember as a sort of Robert Baratheon of the Ming dynasty, later commentators such as Zhang Zhupo 張竹坡 (1670-1698) have convincingly argued that the author of the Jin Ping Mei meant for his work to be interpreted as political allegory.2

Nevertheless, biting political allegory of long dead historical figures doesn’t exactly fly off the shelves these days, and for better or worse the Jin Ping Mei has come to be known mostly for the dirty bits. As part of a guest lecture for a class on the book3 I recently delved into the murky world of comic book adaptations of the great novel. Many of these are, unsurprising, porn, plain and simple, while others are “neither meat nor vegetable” 不葷不素. 4

Jin Ping Mei: The Children’s Book

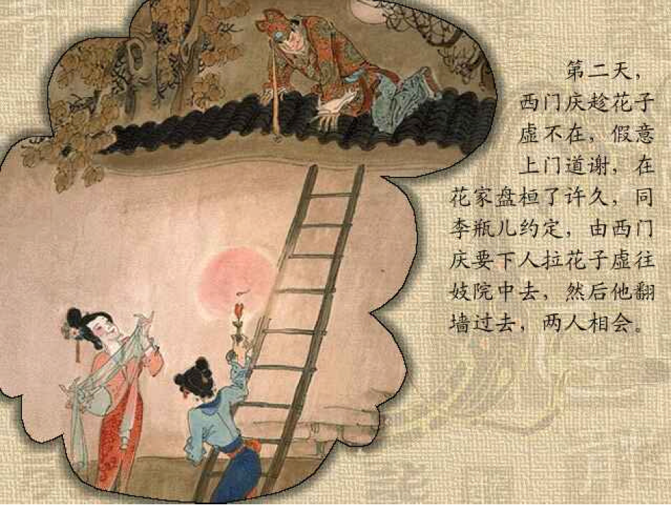

This seems to be the most common illustrated version of the story available online. Although the author and publisher are not identified, although one version identifies as being “for use in schools” (学校专集). In total there are 100 images with abbreviated text to the side in an updated lianhuanhua 連環畫5 style. Also known as 小人書 or ‘children’s books,’ lianhuanhua emerged in the 1920s as a popular form of story-based comics, defined in opposition to manhua (漫畫) or European and North American style newspaper cartoon strips.

In content, the first 85 pages are spent retelling the Wu Song 武松 chapters of the original novel, with the arrival of Li Pinger, the death of Guange, the death of Ximen Qing and the death of Pan Jinlian at the hands of Wu Song compressed into the last 15 pages. Chunmei and her postscript is also largely absent from this adaptation. Not surprisingly, most of the sex and violence in the text is alluded to but not shown in the illustrations.

Jin Ping Mei: The Picture Book

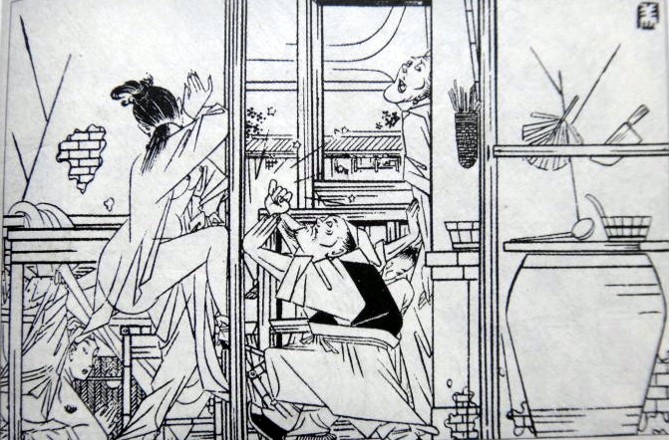

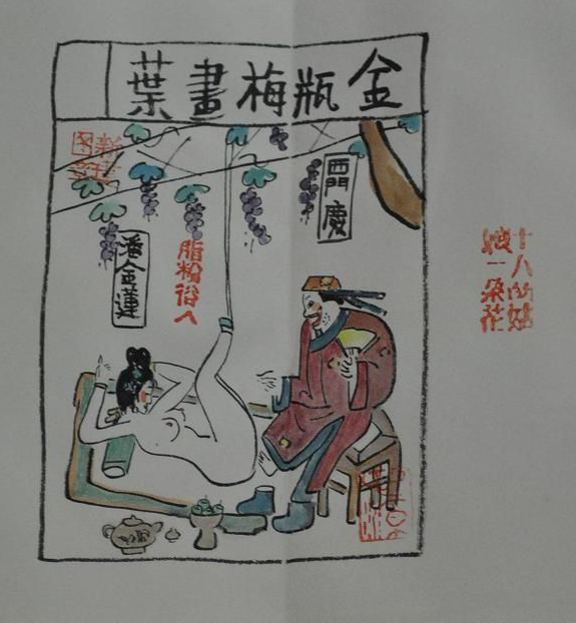

Similar to the above version, this lianhuanhua style adaptation by Cao Hanmei 曹涵美 (1902-1975)6 includes 500 images with abbreviated text underneath. Originally published in Modern Sketch《时代漫画》1934-1937, it was later collected into one volume in 1942.

Interestingly, from what I have seen of this version, it seems to tell the story from the perspective of Pan Jianlian, beginning with her birth. It is also not particularly pornographic, as it seems to focus more on telling the story of the novel rather than just the juicy bits. Nudity also tends to be incidental, as in the panel above. Although Pan Jinlian’s breasts are exposed, they are just one detail in a complex composition.

Cao’s illustrations were also used in the opening credits to Li Hanxiang’s 李翰祥 1974 film adaptation of the Jin Ping Mei, Golden Lotus 金瓶雙艷, starring a very young Jackie Chan 成龍:

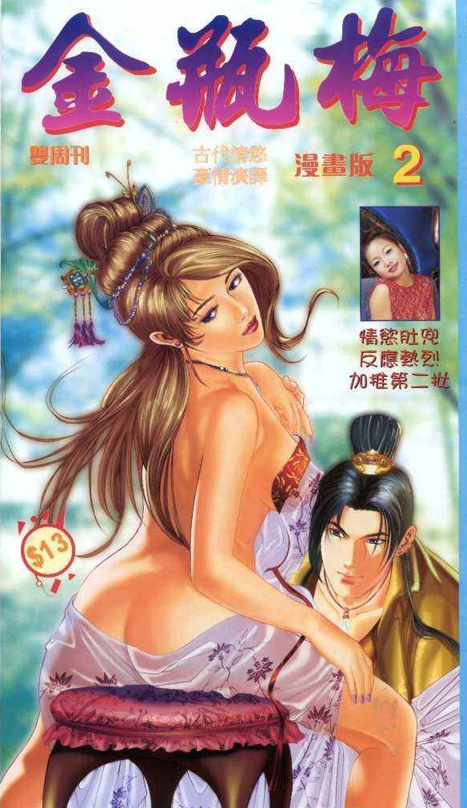

Jin Ping Mei: The Adult Comic Book

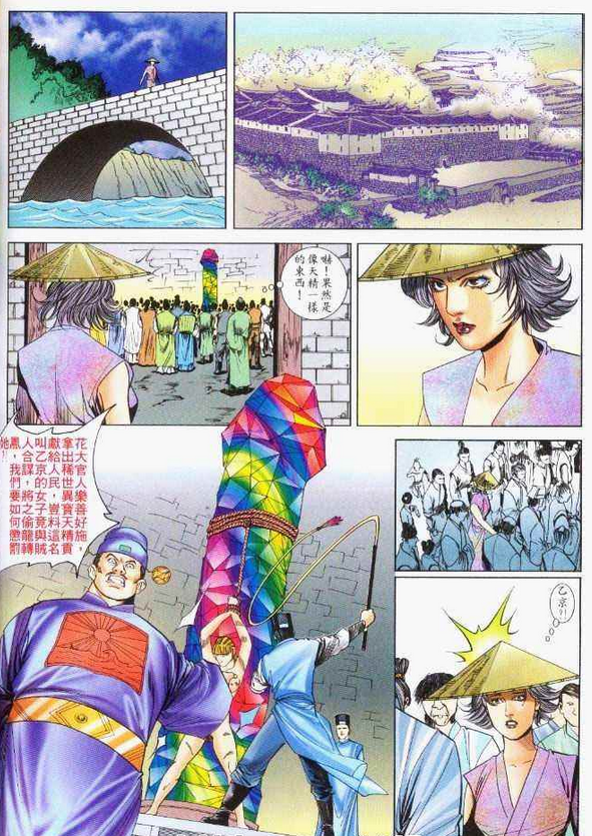

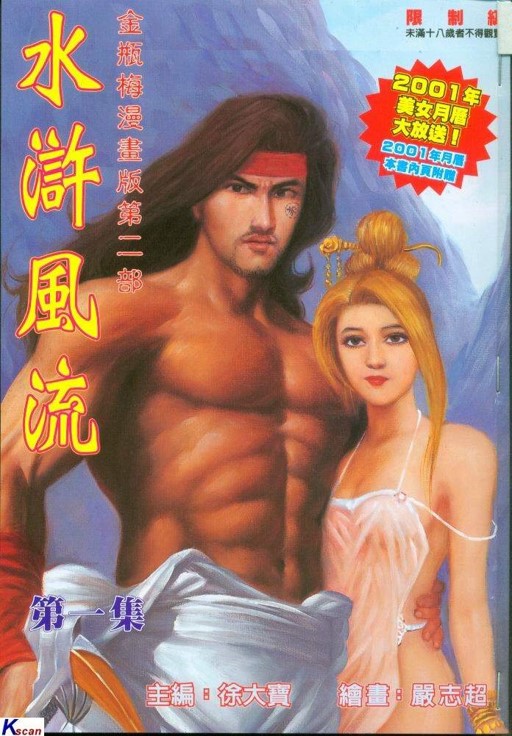

Published in 2000 in Hong Kong by Sun Century in biweekly installments of ~30 pages,with a complete run of 32 volumes, mostly focused on the Wu Song chapters lifted from the Shuihuzhuan. Adapted by Xu Dabao (徐大寶) with art by Yan Zhiqiang (嚴志强), this version is essentially porn, with a heaping spoonful of wuxia [martial chivalry] 武俠 tropes and ‘nonsense’ 無厘頭 humor ala Stephen Chow 周星馳.

Although certain echoes of the original novel exist in the first issue, with Wu Song’s killing of the tiger being juxtaposed with Wu Daolao 武大老 having sex with Pan ‘Tiger’ Jinlian, effectively equating sex with violence, by the end of the series things have gone completely off the rails, with flying yamen guards similar to the characters in Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and the plot now revolving around a giant crystal phallus:

The same artist writer team followed this work with the very tasteful series Gallants of the Water Margin 水滸風流:

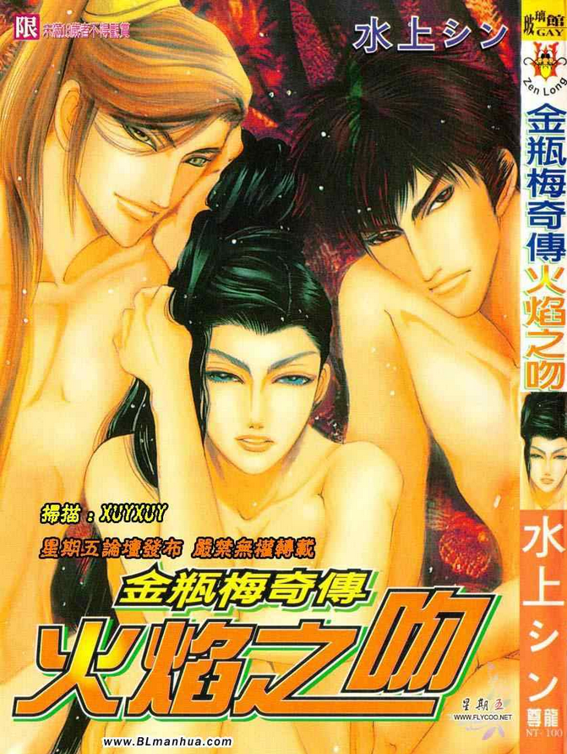

Jin Ping Mei: The Boys Love Manga

Written and drawn by Mizukami Shin (水上シン) and first published in Japan in five installments between September 2003 and January 2004 in the magazine BExBOY by BiBLOS Pressビブロス出版社, Mizukami’s work was later collected into the 191 page single anthology Kinpeibai Kinden Honoo no Kuchizuke 金瓶梅・奇伝 炎のくちづけor The “Strange Tale of the Jin Ping Mei: Kiss of Fire,” published in 2004, it has since been translated into Chinese as Jin Ping Mei qi zhuan huoyan zhi wen 金瓶梅奇傳 火焰之吻 and republished in Taiwan by Zen Long Press 尊龍出版社, a prolific publisher of (reputedly) pirated Japanese comics.7 This pirated version has itself been pirated and is widely available online, stripped of copyright and publication information.

As is apparent from the cover, like many dōjinshi 同人誌, or amateur Japanese comics, it is a work of ‘slash’ fan fiction, known in Japan as “Boys Love.” In this ~200 page retelling homosexual love story, the original novel is transformed from a cautionary tale into a romance between (a male) Pan Jinlian, Wu Song, Wu the Elder and Ximen Qing 西門慶. The audience for BL manga in Japan is predominantly female, and this seems to also be the target demographic for this book:

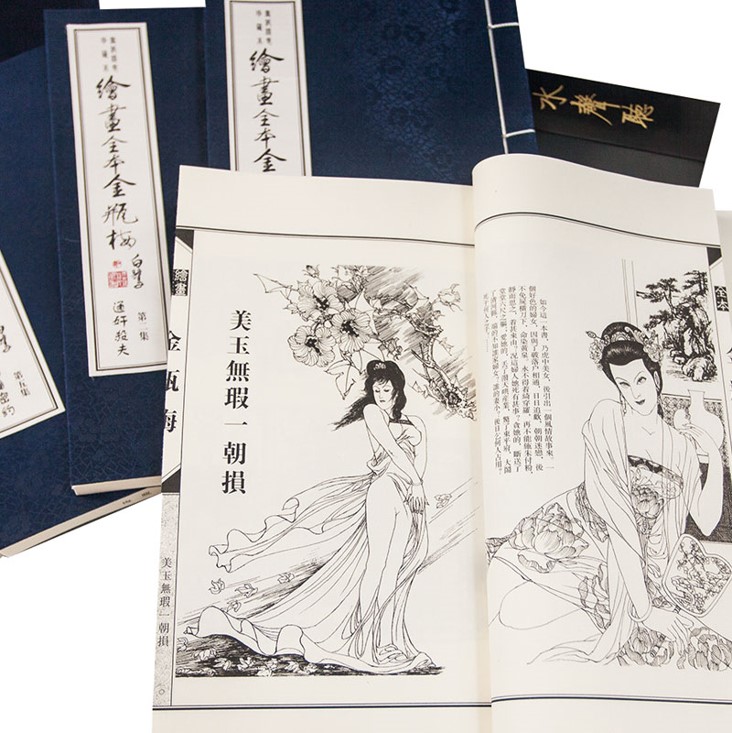

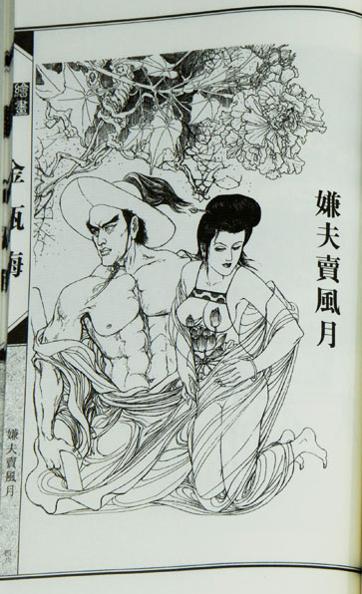

Jin Ping Mei: The Complete Illustrated Edition

This illustrated version consists of 21 volumes published in a limited run of 300 by People’s Publishing Ltd 民眾出版社 in Hong Kong in 2013, with art by the totally-not-pseudonymous White Egret 白鹭 and a suggested retail price of $1580 USD. While extremely high cost and limited would seem to indicate this is meant for connoisseurs, in English it is marketed as the “Graphic Novel Chin P’ing Mei.”

Not having a grand and half to drop on pornographic comics, I can’t say much about this adaption, other than to note that like Xu Dabao and Yan Zhiqiang’s adaptation it seems to show an influence of wuxia comics in treatment of the male body:

Jin Ping Mei: The Artist’s Monograph

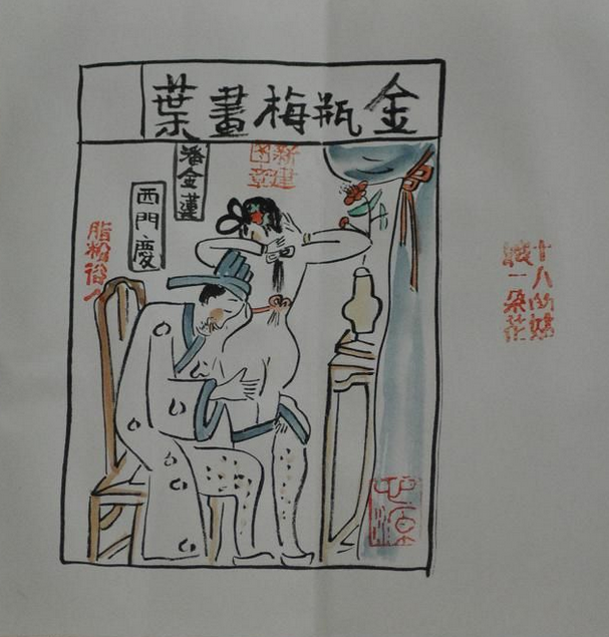

Another work that clearly is designed for connoisseurs, copies of this collection of watercolors by Zhu Xinjian 朱新建 (1953-2014) sell for $800 online. Zhu began his career as a character designer for children’s cartoons and became famous for his erotic drawings of ‘small-footed women’ 小脚女人 which combine manga and traditional Chinese ink painting aesthetics.

Given the credentials of the artist, and the unique artistic style it seems easier to accept this work as ‘art,’ in many ways calling to mind Feng Zikai’s 1920s manhua or ‘casual drawing.’ Still, it is very undeniably pornographic, focusing on just the dirty bits:

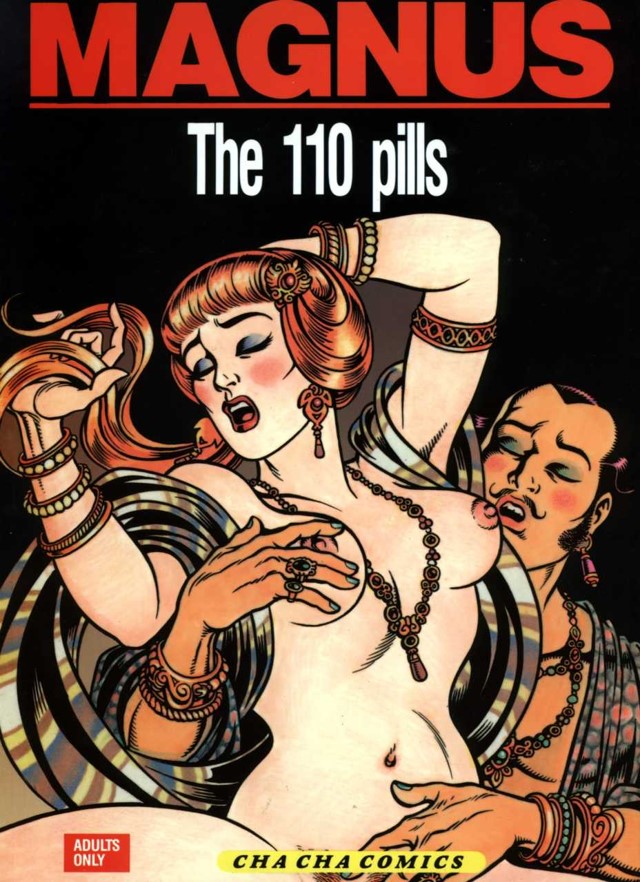

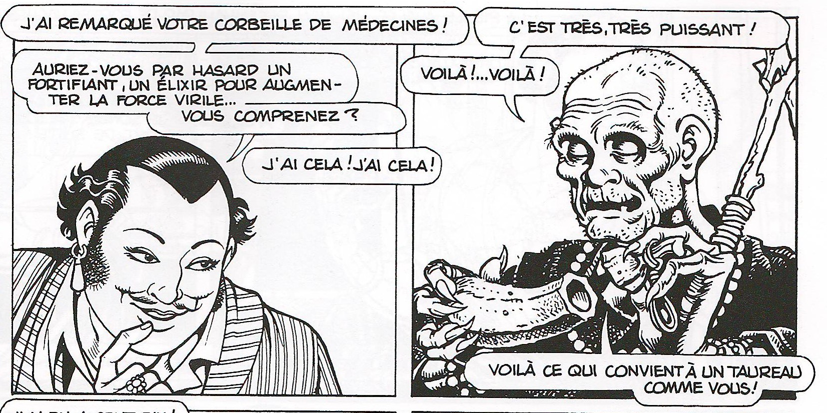

Jin Ping Mei: The 110 Pills

Written and illustrated by the Italian comic book artist Roberto Raviola (aka Magnus) (1939-1996) in 1985 and first published in English by Cha Cha Comics in 1990. Magnus had previously completed The Brigands (I Briganti, 1973-1978) a loose adaption of Shuihuzhuan set in the distant future. This led to creating the Chinese influenced sci-fi comic Milady 3000 (Milady nel 3000, 1980) for the influential French magazine Metal Hurlant, and eventually The 110 Pills, a surprisingly faithful adaption of the Jin Ping Mei.

Interestingly this is one of the only adaptions I have seen in which Ximen Qing dies of sexual exhaustion, aside from the two lianhuanhua adaptions (although presumably the Complete Illustrated Edition would also contain this plot point) The only real problem with this work is that Ximen Qing looks more Indian than Chinese, especially in the way he is dressed:

Also, it’s almost completely pornographic with very little of the non-sexual plot included, but as the above examples amply demonstrate, that seems to come with the territory.

- In the earlier Wade-Giles transliteration still preferred by many academics it is rendered ” Chin P’ing Mei.” David Roy includes the literal translation, “Plum in the Golden Vase,” as the subtitle to his version although the accuracy of this is disputable, given that the title is generally assumed to refer to the names of three most important female characters: Pan Jinlian 潘金蓮, Li Ping‘er 李瓶兒 and Pang Chunmei 龐春梅. [↩]

- Chang, Chu-p’o. “How to Read the Chin P’ing Mei.” In How to Read the Chinese Novel, edited by David Rolston, translated by David Tod Roy, 196–201. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1990. [↩]

- ASIA 441B taught by the incomparable Catherine Swatek who also happens to be David Roy’s cousin. [↩]

- In other words, neither fish nor fowl. [↩]

- Abbreviation of lianhuatuhua 連環圖畫 or ‘linked-picture’ books [↩]

- Given name Zhang Meiyu (张美宇), middle brother of the more famous cartoonists and publishers Zhang Guangyu 张光宇 (1900-1965, née Zhang Dengying 张登瀛) and Zhang Zhengyu 张正宇 (1904-1976, née Zhang Zhenyu 張振宇). [↩]

- The pirating of Japanese comics in Taiwan seems to have begun in the 1960s when censorship laws unfairly targeted local cartoonists and, ironically, favored imported Japanese comics. Comic industry heavyweight Tong Li Publishing東立出版社, for example, reportedly got its start when cartoonist-cum-entrepreneur Fan Wan-nan范萬楠began printing large runs of pirated Japanese comics in the 1970s and 80s. Although the situation was rectified somewhat when the Taiwanese government signed a bilateral copyright agreement with Japan in 1992, from the large catalog of works produced by Zen Long and other pirate publishers it seems clear that sexually explicit works which fall outside of the mainstream, such as Kiss of Fire, continued to be pirated with impunity. This de facto tolerance of copyright violations for pornographic works was made de jure after a 2013 ruling by the Taipei District Court which rejected a case put forth by a consortium of Japanese adult film producers against the Taiwanese web aggregator ELTA Technology Co., Ltd 愛爾達科技 on the grounds that while works of literature, science and the arts are subject to intellectual property laws in Taiwan, works which “feature oral and other forms of sex… [and] aim to arouse viewers’ desires” are pornography and therefore are not afforded any protection under Taiwanese law. See John A. Lent, Pulp Demons: International Dimensions of the Postwar Anti-Comics Campaign (Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1999), 195; “Firms Avoid Prosecution over Adult Films – Taipei Times,” accessed May 2, 2014, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2013/03/23/2003557791. [↩]

Pingback: High-of-the-Week Hyperlinks: Bother in Vietnam, the Nice Wall Marathon, and China’s new Liu Xiang? | That's Beijing - Beijing and China News

Pingback: The Many Faces of Sun Wukong: Three Classic Cartoon Adaptations of Journey to the West - Nick Stember