The Jin Ping Mei 金瓶梅1 is a notoriously pornographic vernacular Chinese novel believed to date from the late sixteenth century. Authored during the disastrous reign of the Wanli Emperor 萬里 who posterity has come to remember as a sort of Robert Baratheon of the Ming dynasty, later commentators such as Zhang Zhupo 張竹坡 (1670-1698) have convincingly argued that the author of the Jin Ping Mei meant for his work to be interpreted as political allegory.2

Nevertheless, biting political allegory of long dead historical figures doesn’t exactly fly off the shelves these days, and for better or worse the Jin Ping Mei has come to be known mostly for the dirty bits. As part of a guest lecture for a class on the book3 I recently delved into the murky world of comic book adaptations of the great novel. Many of these are, unsurprising, porn, plain and simple, while others are “neither meat nor vegetable” 不葷不素. 4

Jin Ping Mei: The Children’s Book

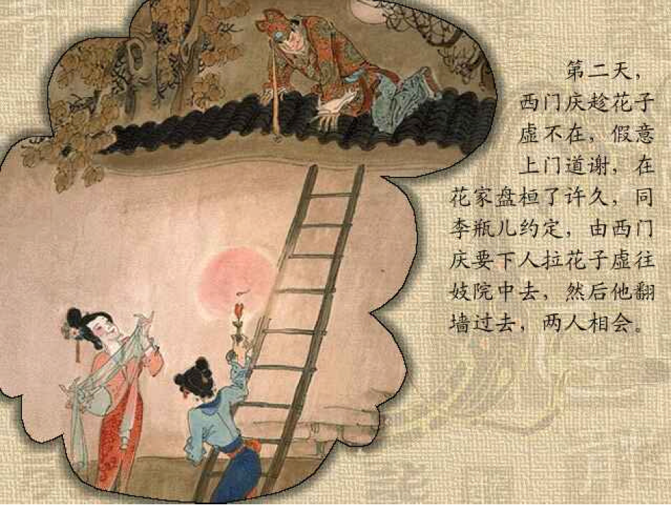

This seems to be the most common illustrated version of the story available online. Although the author and publisher are not identified, although one version identifies as being “for use in schools” (学校专集). In total there are 100 images with abbreviated text to the side in an updated lianhuanhua 連環畫5 style. Also known as 小人書 or ‘children’s books,’ lianhuanhua emerged in the 1920s as a popular form of story-based comics, defined in opposition to manhua (漫畫) or European and North American style newspaper cartoon strips.

In content, the first 85 pages are spent retelling the Wu Song 武松 chapters of the original novel, with the arrival of Li Pinger, the death of Guange, the death of Ximen Qing and the death of Pan Jinlian at the hands of Wu Song compressed into the last 15 pages. Chunmei and her postscript is also largely absent from this adaptation. Not surprisingly, most of the sex and violence in the text is alluded to but not shown in the illustrations.

Jin Ping Mei: The Picture Book

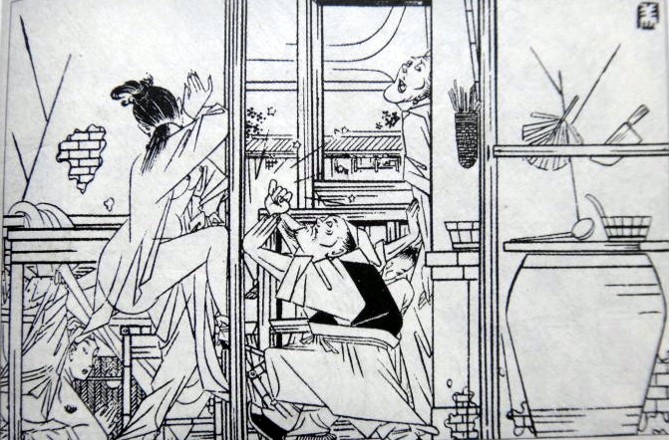

Similar to the above version, this lianhuanhua style adaptation by Cao Hanmei 曹涵美 (1902-1975)6 includes 500 images with abbreviated text underneath. Originally published in Modern Sketch《时代漫画》1934-1937, it was later collected into one volume in 1942.

Interestingly, from what I have seen of this version, it seems to tell the story from the perspective of Pan Jianlian, beginning with her birth. It is also not particularly pornographic, as it seems to focus more on telling the story of the novel rather than just the juicy bits. Nudity also tends to be incidental, as in the panel above. Although Pan Jinlian’s breasts are exposed, they are just one detail in a complex composition.

Cao’s illustrations were also used in the opening credits to Li Hanxiang’s 李翰祥 1974 film adaptation of the Jin Ping Mei, Golden Lotus 金瓶雙艷, starring a very young Jackie Chan 成龍:

- In the earlier Wade-Giles transliteration still preferred by many academics it is rendered ” Chin P’ing Mei.” David Roy includes the literal translation, “Plum in the Golden Vase,” as the subtitle to his version although the accuracy of this is disputable, given that the title is generally assumed to refer to the names of three most important female characters: Pan Jinlian 潘金蓮, Li Ping‘er 李瓶兒 and Pang Chunmei 龐春梅. [↩]

- Chang, Chu-p’o. “How to Read the Chin P’ing Mei.” In How to Read the Chinese Novel, edited by David Rolston, translated by David Tod Roy, 196–201. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1990. [↩]

- ASIA 441B taught by the incomparable Catherine Swatek who also happens to be David Roy’s cousin. [↩]

- In other words, neither fish nor fowl. [↩]

- Abbreviation of lianhuatuhua 連環圖畫 or ‘linked-picture’ books [↩]

- Given name Zhang Meiyu (张美宇), middle brother of the more famous cartoonists and publishers Zhang Guangyu 张光宇 (1900-1965, née Zhang Dengying 张登瀛) and Zhang Zhengyu 张正宇 (1904-1976, née Zhang Zhenyu 張振宇). [↩]