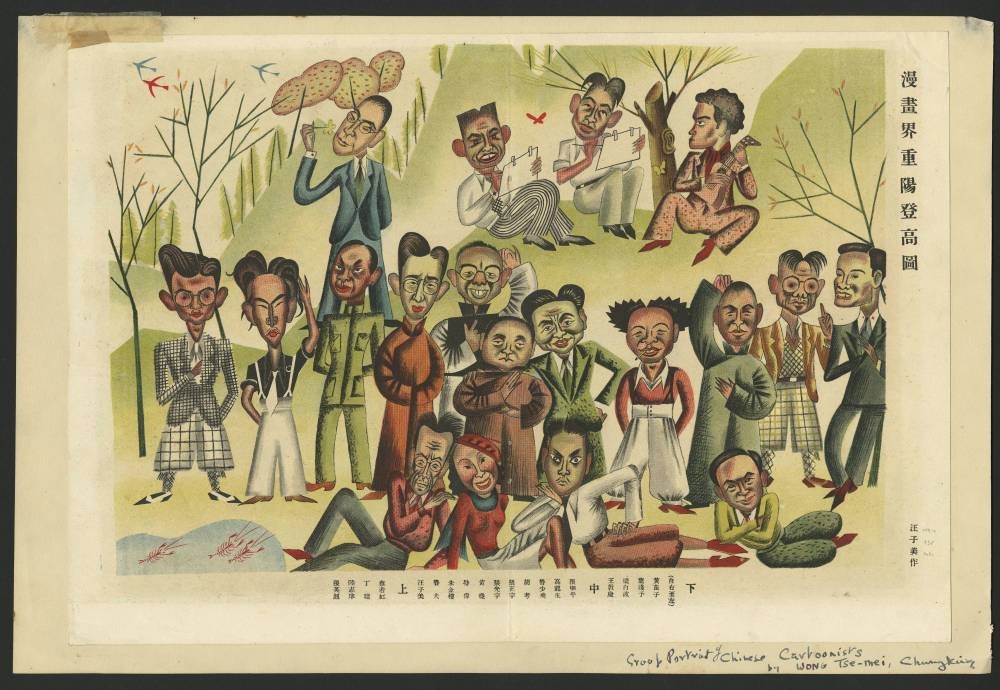

In my post on cartoon versions of Sun Wukong, I discussed Zhang Guangyu’s 張光宇 (1900-1965) overlooked masterpiece, Manhua Journey to the West 西遊漫記. Originally created in the fall of 1945 while Zhang was living in the wartime capital of Chongqing, Manhua Journey to the West was initially introduced to the public through a series of popular exhibitions in Chongqing, Chengdu, Shanghai and Hong Kong. Due to both the limitations of the print industry at the time, and eventual KMT censorship, and the turmoil accompanying the founding of the PRC it was not until 1958 that a book version was finally released by the People’s Fine Arts Press 人民美術出版社出版 in Beijing. In 1998, over three decades after Zhang’s death in 1965, it was republished Shandong Pictorial Press 山東畫報出版社, and from December 25, 2012 to February 24, 2013, the original artwork was put on display in as part of a larger retrospective exhibition of Zhang’s work at the Suzhou Museum 苏州博物馆.

My own exposure to the work came several months ago while reading a recently published collection of essays dedicated to Zhang Guangyu and his works. Before reading this collection, I had primarily thought of Zhang both as a magazine editor and also as an organizer of various influential cartoonists’ organizations. Aside from several memorable covers of Modern Sketch 时代漫画and other magazines he was involved in during the 1930s, I had not seen much of his work as an artist. Fortunately, along with the essays, the editors choose to reprint examples of not only his covers, but also selections from his full color comics, including two pages from the Manhua Journey to the West. Zhang does not seem to have done much work in black in white, nor does he seem to have had much interest in doing simple gag strips. This may explain why he is less well known than cartoonists such as contemporaries Zhang Leping 张乐平 and Feng Zikai 丰子恺, whose black and white cartoons can be easily and cheaply reproduced without much loss in quality. Even online, color works tend to fair more poorly in transmission, since many colors cannot be accurately reproduced by the compressed image file formats which are most commonly used.

Not having access to the original book, or a reprint thereof, however, curiosity drove me to seek out an online version of Manhua Journey to the West. After almost giving up, I was finally able to find a Chinese-language art blog which had reposted the entire series of drawings, with the narration included as text below the image. For the sake of introducing Zhang’s out-of-print work to a larger audience, I’ve translated the 60 page text, as recorded on that blog, with a few edits for what seem to be transcription errors. Enjoy!

Manhua Journey to the West: Part 1, written and illustrated by Zhang Guangyu 張光宇

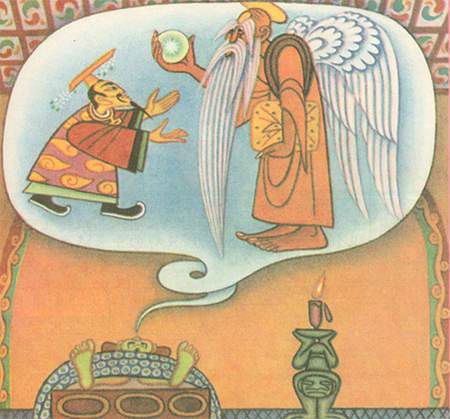

1. 话说古时有个国王,掌理朝政,精明能干;有一夜梦里见历史老人手拿一个圆球,一手执着一册天书扬言道:“世界之大,无奇不有,你这小小的王国,算得了什 么?我把这球赠汝,将去仔细观看,里面自有千变万化!”言罢把球郑重递与国王,国王接过来待又问:“你这本天书也能送给我吗?”老人道:“慢来!慢来!” 说罢便不见了形迹。

It is said that in ancient times there was a king, who was capable and efficient in dealing with affairs of state; in a dream he saw Father Time carrying a sphere in one hand, and in the other a celestial tome, warning him, “In the vastness of the world, there is no limit to the extraordinary things that exist. What does your teeny tiny kingdom amount to compared to all of this? I gift this sphere unto you, study it closely, for it contains the myriad changes and the countless permutations!” His words completed, he handed the sphere to the king, who took it asking, “Will you gift your celestial tome to me as well?” Father Time said, “One thing at a time! One thing at a time!” and with that, disappeared.

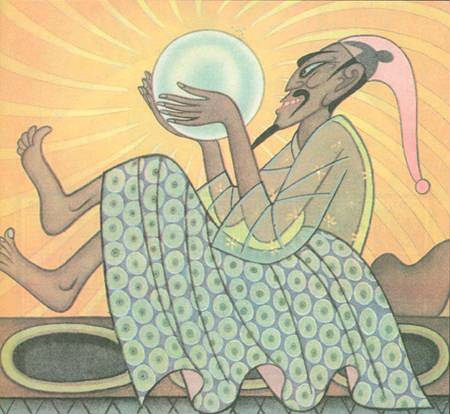

2. 国王从梦中惊醒,那个圆球果然还在手中,仔细一看,原来是个浑圆水晶球,上面没有什么东西可看,只见球的中心透亮发光,渐渐的显出花样来了。

The king awoke from his dream only to discover that the sphere was still in his hands. Studying it closely, he found that it was a perfectly round crystal ball, with nothing visible on its surface, aside from the fact that the center of the sphere was translucent and glowing. Slowly but surely patterns began to emerge.

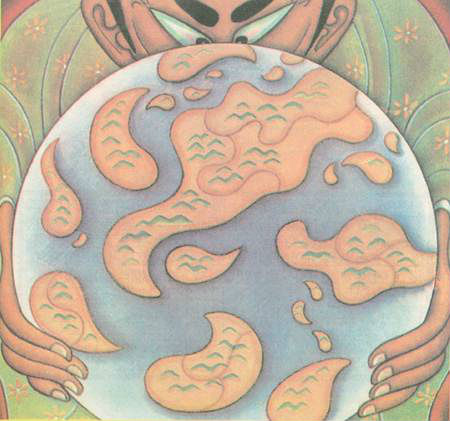

3. 原来是一幅“山海舆地图”,连自己的王国也发现在一个角落里。

It turns out that it was a “map of the mountains and seas,” in one corner of which he was even able to find his own kingdom.