Seeing that Eric Abrahamsen’s translation of Xu Zechen’s Running Through Beijing was released by Two Lines Press earlier this month, it seems appropriate to sketch out a tradition of movie pirating that existed in mainland China before the advent of bootlegged DVDs:

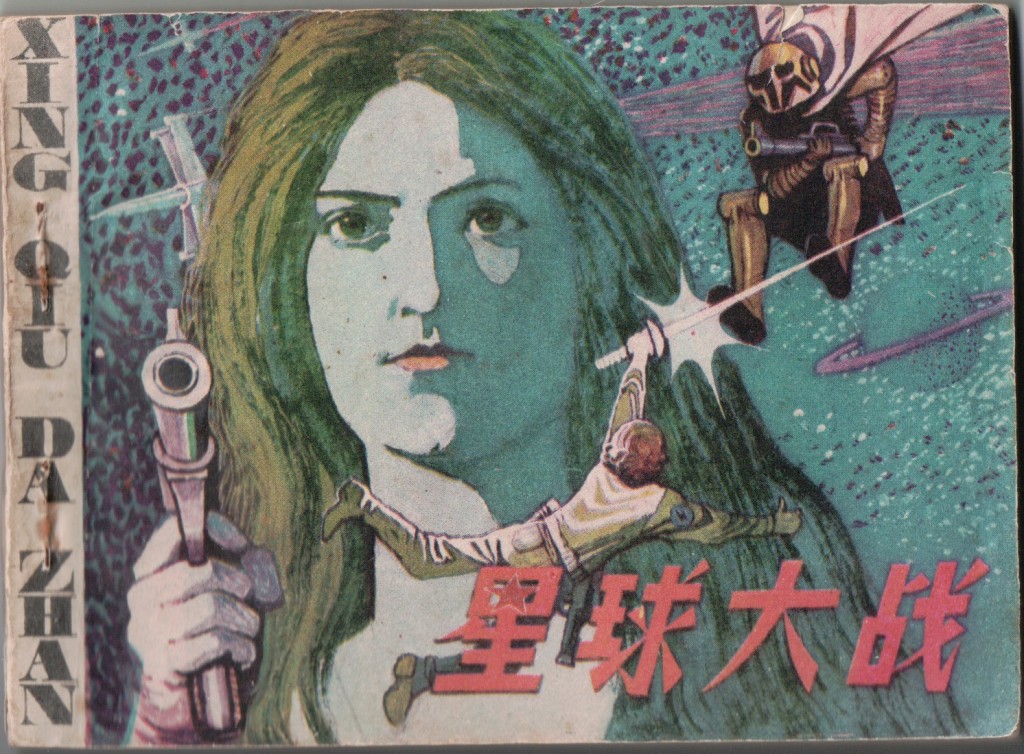

This is a lianhuanhua 連環畫 adaptation of Star Wars which historian Maggie Greene picked up at the infamous Wen Miao 文廟 book market in Shanghai in 2011. She recently posted a complete scan to her blog The Wayward Historian, which Brendan O’Kane OCRed and reposted here. According the copyright (sic) page, this work was published in December, 1980, by Yuebei Press 粵北印刷廠 and distributed by the Guangdong branch of the state-owned Xinhua Bookstore 廣東省新華書店, with editing by Zhou Jinzhuo 周金灼 and illustrations by Song Feideng 宋飛等.

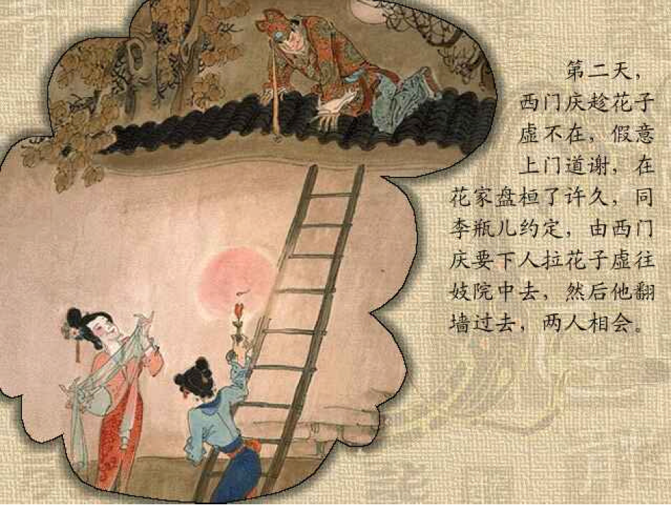

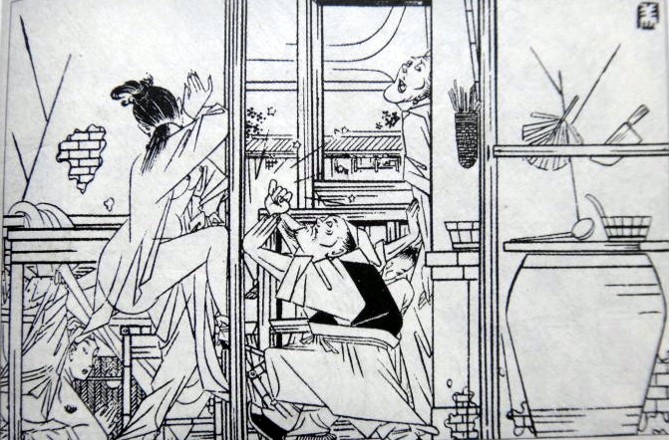

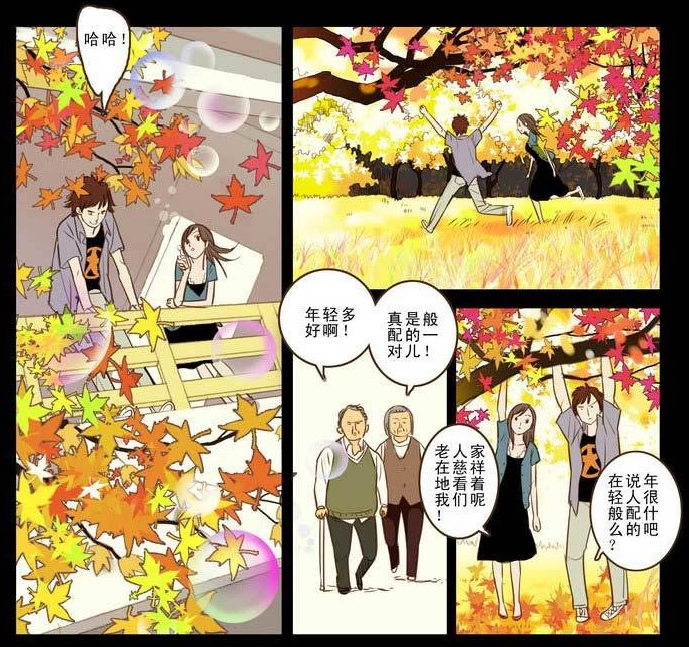

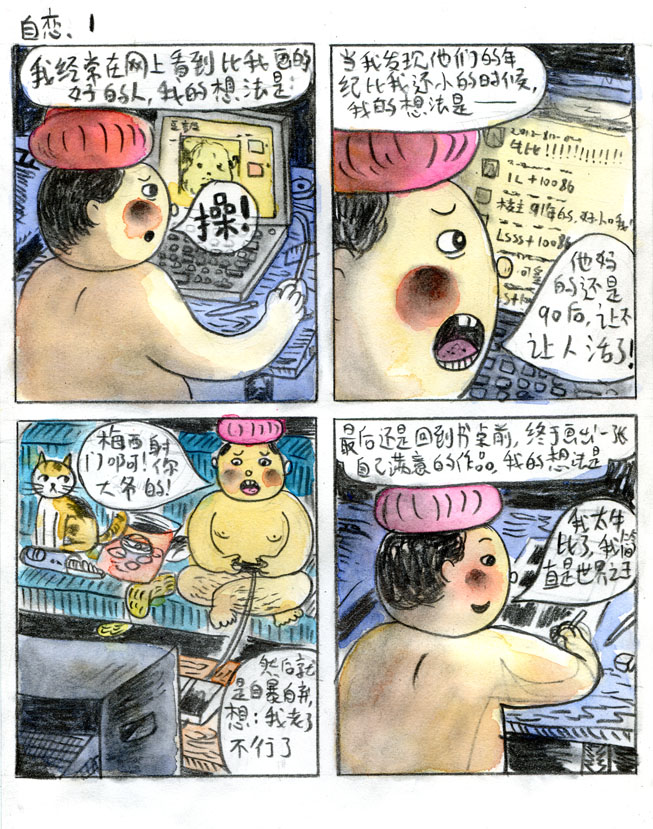

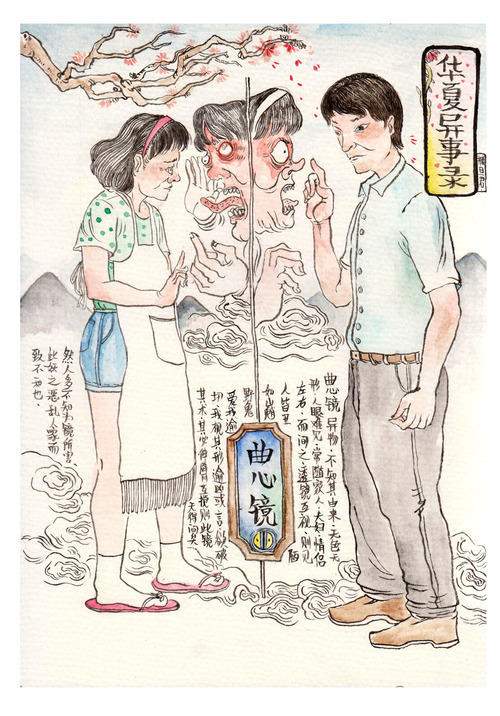

Lianhuanhua, or “linked picture books,” have been around since roughly the turn of the 20th century, when cheap printing technology made it possible for publishers to mass produce high fidelity images and text at low cost, providing a new form of entertainment for growing numbers of literate urbanites.1 As comics historian Paul Gravett described them in a 2008 interview for the Manhua! China Comics Now Exhibition2 (appropriately introducing an unauthorized 1984 lianhuanhua adaption of Hergé’s The Adventures of Tintin: The Blue Lotus ):3

What I’m going to show you here, this is actually what Chinese comics came from. Chinese comics, before they were called manhua they were called lianhuanhua, which means, basically, the hua means drawings and the lianhuan means linked up, joined together in a chain. So it’s like, comics in sequence, or drawings in sequence. And they appeared in color, and in black and white, particularly in this format and also in larger format books, with one image per page, often with the text appearing underneath. But interestingly, they did actually use speech balloons as well. As we see here there are examples of it. And they were cheap; even if you couldn’t afford them you could actually sit in the street and rent them. Literally, you’d read them in the street, there’d be some chairs, there’d be a guy with a whole shelf loan of these little tiny comics, and you could read them. Because of course some of these comics run for several volumes, maybe, ten, twenty, thirty volumes, and you could read them all in one sitting, just like manga cafes now. Just like the way manga’s gone now—that was already going on back in the twenty and thirties.4

Although it is somewhat misleading to say that lianhuanhua proceeded manhua, as both emerged more or less contemporaneously as distinct forms of production, Gravett correctly points out that it wasn’t until the 1920s and 30s that lianhuanhua really took off, and that for most of its history lianhuanhua was something that you would rent rather than own. Due to their inherent disposability relatively few of the earliest lianhuanhua have survived. That said, one which did seems to indicate that the tradition of adapting American movies to lianhuanhua is older than we might think:

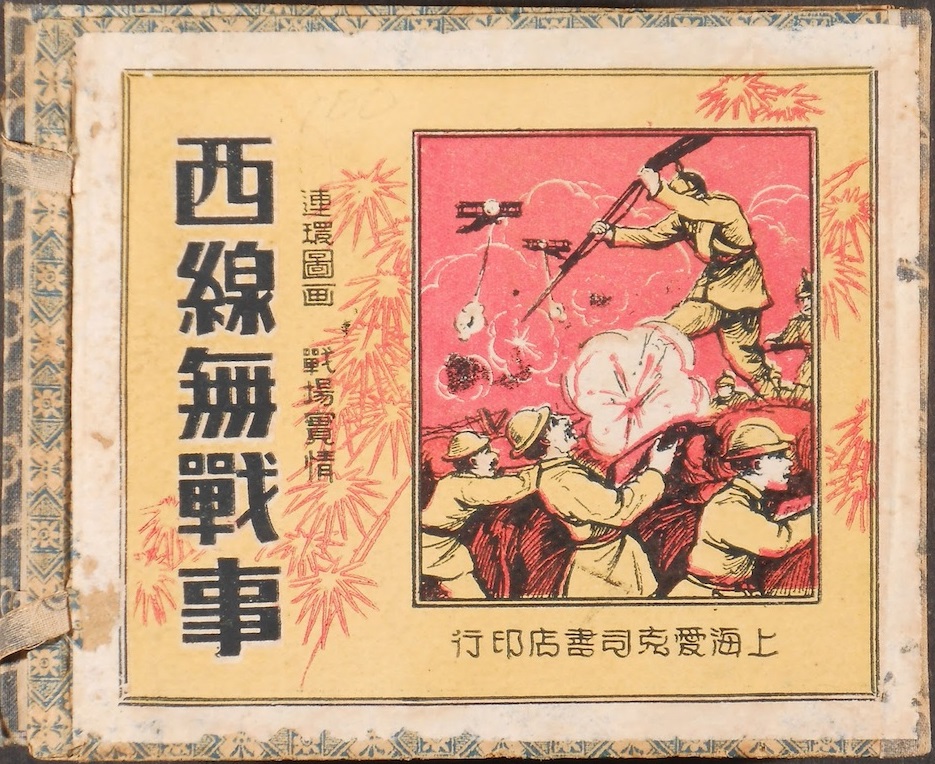

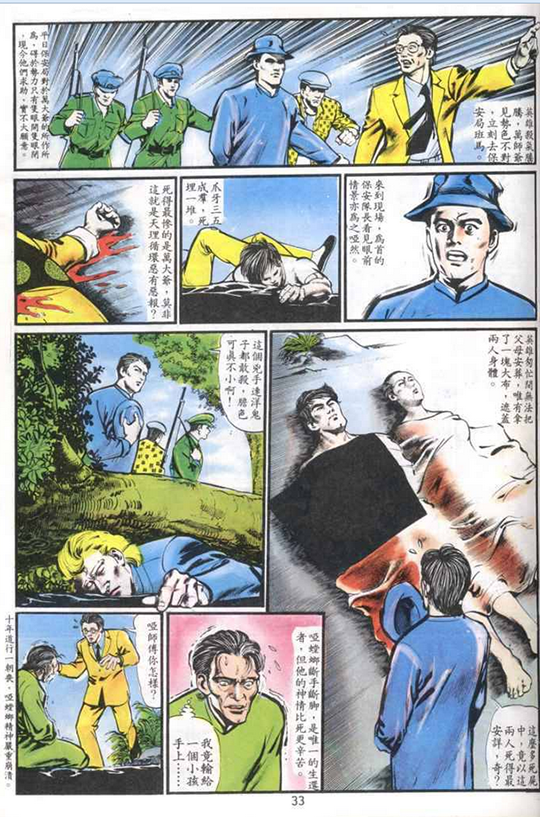

All Quiet on the Western Front 西线无战事 published in the 1930s by Shanghai Aikesi Bookstore 上海爱克司书店, adapted from the original, translator and artist unknown.

This is a lianhuanhua adaptation of WWI veteran Erich Maria Remarque’s bestselling novel Im Westen nichts Neues, first serialized in 1928 and later translated into English by Arthur Wesley Wheen in 1929 as All Quiet on the Western Front. Presumed to pirated, this adaptation appears to have been based on the 1930 American film version directed by Lewis Milestone which was released in China only to be banned along with all other “anti-war” films by the Nationalist government in 1934.5 Curators at the Rauner Library Special Collections at Dartmouth which purchased the adaption in 2013 have pointed out that although antiwar films were banned in China, versions of the story continued to circulate in Shanghai as a form of “cultural resistance.” Moreover, despite reports which indicate that attendance for anti-war films such as All Quiet on the Western Front was poor,6 the existence of this work shows that its anti-war message must have held some appeal.7

- For a history of the medium, see Shen, Kuiyi. “Lianhuanhua and Manhua – Picture Books and Comics in Old Shanghai.” In Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books, edited by John A. Lent, 100–. University of Hawaii Press, 2001. [↩]

- This exhibition ran twice, first at the London College of Communication from March 7 to April 11, 2008, and then again the next year at Durham Oriental Museum from May 2 to September 27, 2009, and included over 200 examples of Chinese comics and cartoons. [↩]

- Hergé [埃爾熱], Lan Lianhua – Ding Ding Lixian Ji (Shang)藍 蓮花—丁丁歷險記 (上) [The Blue Lotus – The Adventures of Tintin (Vol 1 of 2)], trans. by Binggang Li [李秉剛] (Beijing: Zhongguo Wenlian Chubanshe, 1984), Beijing; Hergé [埃爾熱], Lan Lianhua – Ding Ding Lixian Ji (Xia)藍 蓮花—丁丁歷險記 (下) [The Blue Lotus – The Adventures of Tintin (Vol 2 of 2)], trans. by Binggang Li [李秉剛] (Beijing: Zhongguo Wenlian Chubanshe, 1984), Beijing. [↩]

- Alex Fitch / Paul Gravett, Panel Borders: Manhua! China Comics Now Part 1, 2008 <http://archive.org/details/PanelBordersManhuaChinaComicsNowPart1> accessed 16 April 2014 [↩]

- Zhu, Ying, and Stanley Rosen, eds. Art, Politics, and Commerce in Chinese Cinema. Hong Kong University Press, 2010, 66 [↩]

- Ibid. [↩]

- Rebecca Onion also draws this connection in her short article on Slate “All Quiet on the Western Front: The Book Translated into Chinese Lianhuanhua.”, which I found via the China Books blog post “Chinese Graphic Novels or ‘Lianhuanhua’ « China Books,” both accessed May 23, 2014. [↩]